The Native Mexican Diaspora of Uto-Aztecans

History recalls the Colombian exchange as one of the most influential events in human history, The year 1492 marked the beginning of European colonization in the Americas. For thousands of years, isolated Indigenous Amerindians flourished in the Americas, with an estimated population of between 50 and 100 million, representing well over 1,000 different cultures. The regions of Mesoamerica and the Andes were birthplaces of advanced civilizations that contained large cities supported by agriculture that rivaled Europe. European colonization, however, would rapidly change the Americas, as a major decline in the native population unfolded from disease, war and forced labor. Millions of Europeans would migrate to the Americas for the next 400 years and with them came millions African slaves, and smaller Asian populations.

Native Diasporas of Uto-Aztecans

These diasporas have allowed people to believe that Native Americans never had the opportunity to have their diasporas beyond the Americas. In reality, multiple native American cultures ventured beyond their homeland due to colonization. This article will focus on three Uto-Aztecan speaking cultures: Mexicas (Aztecs), Tlaxcalltecas, and Yoeme (Yaquis) that perhaps had the largest diasporas of all Native Americans. Some notable diasporas will show how these cultures' resilience and contributions went beyond their homelands to new places such as Europe, Asia, and Africa.

The Mexica (Aztec) Empire

The Mexicas or Aztecs are well-known to have established one of the most powerful civilizations. However, before they reached their pinnacle, they came from humble beginnings and their origin starts with the first diaspora. According to their history, their original homeland was a place called Aztlán, which has been debated to be in Western Mexico, Northwestern Mexico or the American Southwest. Sometime around 1000 A.D., they headed south to the Valley of Mexico where they established their future capital city Tenochtitlán in 1325. The Mexicas indeed had a long journey but their travels did not end in the Valley of Mexico,

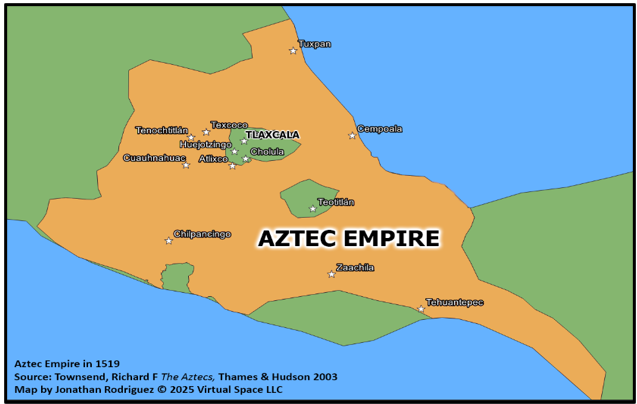

The Aztec Empire At Its Pinnacle

The Aztecs grew in population and so did their military might. Their conquests would extend to both oceans controlling the majority of central Mexico and into Soconusco region of Chiapas and southwestern Guatemala. As they conquered far away lands, the Aztecs would send settlers from Tenochtitlán and other Mexica cities to these new conquered cities, allowing them to have their own people to provide intelligence and learn from the different cultures. By 1519, it is estimated that the Aztecs must have had an Empire as large as 80,000 square miles with a population of roughly 5 to 6 million people, containing many different native languages and ethnicities. Their conquest was just one of many achievements, but their domination created enemies and some native peoples saw opportunities to end their rule.

The Tlaxcaltecas and Their Alliance With the Conquistadors

The Tlaxcaltecas were a sister culture of the Mexica who had also come from Aztlán. However, despite their common origin, the two remained bitter rivals throughout their history, only appearing to unite briefly against another sister culture: the Tepanecas in 1428. The Tlaxcaltecas are said to have been pushed out of the Valley of Mexico in the 13th century and settled east in the modern day state of Tlaxcala. In Tlaxcala, they established Tepeticpac and other cities that united to conquer nearby towns, eventually having a nation about the size of the modern day state.of Tlaxcala. The Tlaxcaltecas would never come close to matching the might of the Aztecs as their nation was completely surrounded by the Aztec Empire.

The Districts of Tlaxcala

This blockade made trade and acquiring resources difficult for Tlaxcala. It likely that the Aztecs had considered the possibility of eventually conquering the Tlaxcaltecas in the future. Conquistador intervention would prevent this fate as the Spaniards landed in Veracruz in 1519. Hernán Cortés and his Conquistadors had heard of the riches in Tenochtitlan and marched west eventually entering Tlaxcala where they were met with a hostile force. The Tlaxcaltecas had first attacked the Conquistadors as a response to these strangers. But days later, the Tlaxcaltecas decided to join the Conquistadores in hopes of changing the power structure of Mesoamerica. Two years later, with the assistance of the Tlaxcaltecas and other native allies, as well as disease, the Aztec Empire fell in 1521.

The Aftermath of the Conquest

The aftermath of the Conquest would devastate the native population as 80% to 90% of Central Mexico’s inhabitants would perish. The survivors would become subjects of the Spanish Crown, and many of them became forced laborers and soldiers for the Spanish Empire. The Tlaxcaltecas, however, received special privileges for their assistance and remained allies with the conquerors in many of their military conquests. The Tlaxcaltecas are the most documented indigenous Mexican culture to accompany the Spaniards as far north as California and south to Nicaragua.

Aztec Blood in Spain

After the death of the three last Aztec Tlatoanis (Emperors) Moctezuma II, Cuitláhuac and Cuauhtémoc one may assume this was the end of the Aztec Royal Noble [the Aztec Aristocracy]. However, there were still many Aztec Nobles that survived the conquest. Hernán Cortés and the conquistadors saw the opportunity to use intermarriage with the Aztec nobles to their advantage. It was not only to give better status for a Spanish soldier, but also to control the remaining Aztec population. One noble to have survived the conquest was the daughter of Moctezuma, Tecuichpoch Ichcaxochitzin. She would be converted to Catholicism and renamed as Isabella Montezuma.

Isabella had previously been married to an Aztec general and the last two Aztec Emperors, she would end up marrying three Spaniards as the first two died. She would mother a total of seven children, including one son of Hernán Cortés out of wedlock. Her children would intermarry with Spanish nobility, continuing the Aztec royal bloodline in both Mexico and Spain.

Juan Cano de Moctezuma would marry Elvira de Toledo who was from a prominent Spanish family and lived in Caceres, Spain where the Toledo-Moctezuma palace would be established. Other palaces would be established in Spain for the descendants of Isabella Moctezuma, including The Palace of Moctezuma in Ciudad Rodrigo, Salamanca and the Marquises of Moctezuma Palace located in Ronda. Royal titles were given to these descendants by various Kings and Queen Isabella II of Spain. The current title is Duke of Moctezuma de Tultengo.

Fighting for Spain

Under New Spain, despite a major decline in the Indigenous population, the surviving cultures would remain the majority of the population and bounce back from their severe declines. The Spanish government took this opportunity to use their native subjects as labor for extracting resources and also for military support. Various Conquistadors would take their native auxiliary forces throughout the Americas, these forces allowed the Spanish Empire to expand rapidly. In fact, Francisco Vázquez de Coronado had native Mexicans as part of his exploration of the American Southwest during 1540-1542. It has also been theorized that Tlaxcaltecas accompanied the Luna y Arellano Expedition of Florida in 1559. Tlaxcaltecs were also recorded to make it to Cuba and the Dominican Republic in 1583.

In other expeditions, the Indian auxiliary forces were composed of many different cultures. In the case of the conquest of the Yucatán under Francisco de Montejo, native forces were from Xochimilca, Tepeanca, Acolhua, Huexotzingos, Chontal, Popoluca, Zoque, Tabascan, Chiapanec, Zapoteca, Mixteca, Mixe, as well as Lenca and Jicaque natives from Honduras.

Why Did Natives Join the Armies of the Conquistadors?

It may be understandable that the Tlaxcaltecas were willing to join the Conquistadors in their conquests due to their alliance and privileges, but for the other native groups, there were multiple reasons. Many groups were forced to join the conquistadors in chains and were punished with hangings if they fled. Some volunteered as an opportunity to gain benefits, while others would become settlers from the wars or be enticed to migrate from their homelands to influence other unconquered natives to live under New Spain. The Conquistadors continued to use this strategy throughout the Americas which started the diasporas for many native cultures in Mexico.

The Conquest of Guatemala and El Salvador

News of the Aztecs' defeat spread into Oaxaca, and both Zapotec and Mixtec leaders sent ambassadors to submit to Cortes. Months later, Cortés sent Francisco de Orozco and his forces to Oaxaca, where the Zapotec and Mixtec people were pacified. With Oaxaca under their control, the Conquistadors turned their attention further south into the areas now known as Chiapas, Guatemala and El Salvador. News of other Spanish Expeditions were already underway in Panama, Costa Rica and along the coasts of Nicaragua to Guatemala. Cortés would instruct his veteran officer, Pedro de Alvarado — who was present during the conquest of Tenochtitlan — to claim these southern lands. Alvarado would assemble an army of about 6,000 Indian auxiliaries, mostly Tlaxcaltecas, but also Cholultecas, Teapeas, Acolhuas, Xochimilcas, Mexicas. Some Zapotecs and Mixtecs would also join them. They had arrived in the Soconosco region of Chiapas in 1523, pacifying most of the native groups.

During the following year, the Spanish and native force under Alvarado entered Guatemala where they met with fierce resistance from the Kʼicheʼ Mayas. Alvarado's forces would soon ally with another Maya group, the Kaqchikel, who were enemies of the K’iche. The campaign consisted of conquering several cities, including San Francisco Zapotitlán, Quetzaltenango, Iximche, and Atitlán. By June the army had entered modern day El Salvador and had encountered the Náhuatl-speaking Pipil people. At the Battle of Acajutla, Alvarado was injured and retreated back to Guatemala. Pedro would appoint his brother Gonzalo to return to finish the conquest of El Salvador. When Gonzalo de Alvarado returned, the City of San Salvador would be founded in 1525 and three years later the Pipil nation of Cuscatlán fell. With this conquest, communities would be established for the native Mexican allies that had served the Spanish cause so well. This is where the modern day City of Mejicanos, El Savaldor, gets its name from as it was a settlement for the native Mexican allies. Santiago de los Caballeros de Guatemala was another notable city founded for the native forces.

Honduras and Nicaragua

Years before the Conquest of El Salvador, Spanish activities were already unfolding in Honduras. In the early decades of the conquest of Honduras, various Conquistadors fought over the region. Gil González Dávila was the first Spaniard to establish a settlement Puerto de Caballos in 1524. Soon after, Cortés had sent Cristóbal de Olid to claim the land for him; however, Olid had betrayed Cortés and claimed Honduras for himself. Olid would be executed after de las Casas and Dávila joined forces. Cortés arrived the following year, after he had executed the last Aztec Ruler Cuauhtémoc and other Nahua Nobles in Campeche. Cortés would establish new settlements such as Nuestra Senora de la Navidad and Trujillo, but would return to Mexico as his authority was now in question. With the absence of Cortés, Honduras continued to be in a state of conflict because rival Spaniards were fighting each other with little progress. Then, in 1536, Pedro de Alvarado arrived with his indigenous Mexican forces to settle the fighting among the Spaniards. Many Tlaxcallans and other Mexican native allies would establish various communities, most notably in Comayagua, Gracias a Dios, and Camasca. The barrio of Mejicapa in Comayagua is an example of this Mexican influence.

In Nicaragua, Gil González Dávila was the first Conquistador to explore the area in 1522, but soon after he retreated after coming in contact with the Nahua speaking Nicaro culture and the Chorotega (who were Oto-Manguean speakers). During Pedro de Alvarado’s arrival in Honduras, he managed to explore parts of Nicaragua, undoubtedly with his Tlaxcaltecas forces. Tlaxcatlecas were also reported to be called into action during a rebellion in Leon, Nicaragua. In 1549, the Governor of Nicaragua, Pedro de Contreras, had his encomienda system deprived by new laws which motivated his son Hernando de Contreras to kill Bishop Antonio de Valdivieso after he had sacked the Bishop's home. A number of Tlaxcalateca and other native soldiers who were stationed in Guatemala were sent to Nicaragua to end the rebellion.

The Conquest of Northern Mexico

After the fall of the Aztec Empire, news spread throughout the region. The Purépechas of Michoacan, a rival nation of the Aztec Empire, were fully aware of what unfolded in the past years and decided not to intervene. Fearing that the same outcome, the Purépecha King Tangaxuan II sent messengers to Tenochtitlán to submit to Cortés. Cortés would instruct one of his officers, Cristóbal de Olid, with an army of 300 Spaniards and 5,000 natives allies — mostly Tlaxcaltecas but also Mexicas and other Nahuas — to the Purépecha Capital of Tzintzuntzan. However, despite the friendly welcome they received, the Conquistadors would sack the city of its gold and precious metals. The Purépechas would also be instructed to support the Conquistadores with soldiers for their future campaigns. Olid's forces would continue to conquer parts of Jalisco. The Lienzo de Tlaxcala depicts this in two pictures of Jalisco and Tototlan.

Figure 2: The Battle of Totolan, Jalisco [from the Lienzo de Tlaxcala].

As the Conquistadores continued to accumulate wealth and land, the power of Hernán Cortés was also growing. His rivals began to accuse Cortés of multiple violations to the point where King Charles V of Spain requested Cortés to plead his case. Cortés left for Spain in 1528. In his absence his rival Conquistador, Nuño de Guzmán, began his campaigns to gain his own wealth and power. In 1530, Guzmán set off from Mexico City to Michoacán with his army of around 400 Spaniards and 7,000 Nahua Indigenous auxiliary troops (Mexicas, Tlaxcaltecas, Acolhuas, and Huejozincos).

In Michoacán, Guzmán had the Purépecha king (Tangaxuan II) tortured and executed after his demand for gold was not met. After leaving Michoacán, Guzmán and his forces — now with an additional 5,000 Purepecha soldiers — marched into the modern day states of Jalisco, Aguascalientes, Zacatecas, Durango, Nayarit and Sinaloa. This expedition resulted in devastation to the native population they had encountered such as the Totorames and Tahues. During this campaign, multiple cities were established, many from pre-existing native settlements. A strong indication of this is shown in the various Náhuatl places seen throughout the states even where Náhuatl was not the native language spoken.

The Route of Nuño de Guzmán (1530-1531)

The Northern Frontier

Even after the conquest of New Spain’s northern frontier, rebellions were still an frequent occurrence throughout New Spain, and once again the Spaniards relied on their native allies. Notable examples were the Mixtón War (1540-1542) and the Chichimeca War (1550-1590). Mexicas, Tlaxcallatecas, Chalcas, and Otomies were present as soldiers for the conquistadors. Francisco Tenamastle, a Caxcan leader of the Mixtón War, was sent to Spain and put on trial where he defended his actions against the conquistadors. In Spain, he went on to represent his culture in Spain.

Native Soldiers Become Settlers

Once the Conquistadors were able to subdue the local native population, the survivors would be integrated into encomiendas, missions and other institutions. Natives from already conquered regions would become settlers in the new areas. Frequently, the native soldiers would become the settlers of the newly conquered areas, while other natives migrated from their ancestral territory. The mining City of Zacatecas became an example of this as various Indigenous barrios were established for the Mexicas, Acolhuas, Tlaxcaltecas and and Tarascans. The Tlaxcaltecas were notable at becoming the founders of multiple cities along the northern frontier of New Spain. These areas include Zacatecas, Nuevo León, Durango, Coahuila, Jalisco, San Luis Potosi, New Mexico and Texas. Tlaxcatecan recognition is even seen at the San Miguel Mission in Santa Fe, New Mexico where a plaque mentions that the Tlaxcallans built this mission back in 1610. These Tlaxcaltecas established the barrio de Analco (a Náhuatl placename meaning “the other side of the water”) where the mission remains to this day.

Tlaxcalan Settlements in Northern New Spain

The Tlaxcaltecas In South America

In the 1530's, Pedro de Alvarado had heard of the riches in South America and wanted to bring the region under his rule. His relationship with Hernán Cortés had evolved into a bitter rivalry which gave him more reasons to leave the north and gain more political power elsewhere. In 1534, his army of about 4,000 — of whom half were Tlaxcaltecas and smaller number of Mayas — had arrived at the Caráquez Bay in modern-day Ecuador. Alvarado did not know that the land was already claimed by Conquistador Franciso Pizarro. Pizarro's officers, Diego de Almagro and Sebastian de Belalcazar, were present in the area and angered by Alvarado's arrival. The two forces met at Quito, but a battle between the two forces was avoided when Alvarado submitted his supplies — including ships, ammunition, horses, and men — to Diego de Almagro. About 750 Tlaxcaltecas soldiers were also transferred to Almagro and would go on to fight under his command and later they became settlers of Lima and Cusco (Peru) in 1535. Alvarado would return to Guatemala with only 100,000 pesos in exchange for his supplies.

Nahuas in the Philippine Islands

Months before the fall of Tenochtitlán, the first European had landed in the Philippines on March 16, 1521. Ferdinand Magellan, a Portuguese sailor explored the area and claimed the land for Spain. A month later, Magellan would die in the Battle of Mactan after trying to defeat a local leader, Lapulapu. In the following decades, various Spanish expeditions examined the islands but the major effort to colonize the Philippines was started in 1565 by Miguel Lopez de Legazpi who arrived from Mexico. It is said that the crew of Lopez de Legazpi comprised hundreds of men, many of which were not Spaniards. Undoubtedly, since this group was from New Spain it must have comprised Criollos, Mestizos and Indios who later settled at Cebu. The exact known Native Mexican culture would be difficult to determine as by this time the Spaniards referred to all Native Mexicans as Indios Mexicanos. It seems most likely that Tlaxcaltecas arrived and even some Mexicas. Years later this expedition would establish Manilla in 1571, which would become the main city of the Philippines and establish a trade sea route to Acapulco, Guerrero.

The Spaniards would continue to conquer the various cultures of the Philippines and battle other cultures in nearby islands with assistance from their soldiers from Mexico and Latin America. Further proof of Nahua influence in the Philippines is seen in the foods that were exchanged into both cuisines from trade. In addition, many words in Tagalog have loan words from Náhuatl.

The Yoeme (Yaquis)

Another notable indigenous Mexican Diaspora is among the Yaquis of Southern Sonora. Prior to Spanish contact, the Yaquis had an estimated population of 30,000 to 65,000 living in over 80 villages along or near the Rio Yaqui, all of which relied on agriculture. The Yaquis’ first encounter with the Spanish was in 1533, when Conquistador Diego Guzmán and his forces of mostly native auxiliaries and fewer Spaniards entered their territory. This first encounter resulted in a bloody battle preventing Guzmán from advancing further north as his forces retreated southward. This would only be the beginning of a long resistance against colonialism for centuries to come.

The Yaquis however weren't completely against learning from these new arrivals for in 1617, the Yaquis welcomed Jesuit missionaries into their land. The eighty villages were soon reduced to eight pueblos as the Yaquis came to live at the missions and were converted into Christianity. For decades there appeared to be tranquility in Southern Sonora as the Yaquis adapted to mission life, however epidemics began to ravage the native population, and silver was discovered in the town of Álamos. The discovery of silver attracted more settlers to come to Sonora, but it also required a large amount of native labor for extraction. Many Yaquis became miners working in Soyopa and Chinipas near Álamos. Other Yaquis went to Hidalgo de Parral in Chihuahua. In 1740, a Native Revolt among the Yaqui, Mayo, Techuecos, Ocoronis, Ahomes, and Pima occurred. The revolt was due to a lack of mission management and a food shortage, as well as a growing desire for autonomy. Industries in the area, especially mining, had stopped operations. By December of 1740, the leaders of the rebellion were captured which ended the revolt.

The Eight Yaqui Pueblos in Southern Sonora

Yaquis Venture Out of Their Homeland

After the Yaqui revolt, the mission system was not as viable, and resentment towards the Jesuits was growing from mining owners who wanted to use natives for labor. Spanish politicians had also feared the Jesuits gained too much power, influence and control of the natives, resulting in the Jesuits being banished from the Americas in 1767. As the Jesuits were on their way out, the Spanish government was able to encroach on Yaqui lands, further escalating tensions in the relationship. The Yaquis were also documented as migrating to Sinaloa, Durango, and northern Sonora. The Yaquis were reported in Arizona in 1796 when a dozen were reported at the Mission of Tumacácori.

Yaquis Flee to Arizona and Deportations

After Mexico had gained its Independence from Spain (1821), it established that all Natives would become citizens, including the Yaquis. However, this meant that the Yaquis would have to pay taxes. This led to a series of conflicts throughout the 19th century, such as the rebellion of Cajeme in the 1880’s. During this rebellion many Yaquis avoided bloodshed by fleeing to Arizona. In Arizona, the Yaqui refugees found employment across southern Arizona, establishing communities notably in Nogales, Tucson, Yuma, Scottsdale and Guadalupe.

Other Yaquis ventured further into the USA, notably New Mexico, Texas, California and even as far as Oregon. Meanwhile back in Mexico, the Administration of President Porfirio Díaz dealt with the Yaqui conflicts by deporting the Yaquis out of Sonora. In the 1900’s, Yaquis were rounded up and forced to work on the sugar cane plantations of Oaxaca and Henequen plantations of Yucatan. Living conditions at these institutions were horrible as many Yaquis died due to the working conditions. Years later the Mexican Revolution broke out in 1910 due to the various policies of Porfirio Diaz who had been in power for over 30 years. During this time many Yaquis joined various military factions and those who were deported started their journey to return back to Sonora. Even after the revolution ended in 1920 tensions continued as promises to Yaquis were not yet fulfilled.

The Destinations of the Yaquis

In 1921, as Mexico was stabilizing from their revolution, another freedom war broke out on far on the side of the world. Morocco had been under French and Spanish occupation since 1912. Almost a decade later, a military leader Abd el-Krim called for an independence movement where the Moorish and Berber communities would unite with the goal of eliminating colonial rule. This event would be known as the Rif War in which France and mercenaries from Latin America would join the side of Spain. Many Mexicans would join the mercenaries but especially the Yaqui. Mexico saw the opportunity as a way to avoid further tension between the Yaquis. In addition, the fierce warrior sprit of the Yaquis were especially recruited for the war.

At least 500 Yaquis initially were recruited to join the Spanish cause. The first voyage left from Veracruz to Cadiz (Spain) in 1921, where they joined the Spanish Foreign Legion and became part of the 16th company. The Yaquis were present in many operations in the war, including the amphibious landing of the Alhucemas Bay (Al Hoceima). One may see the irony of Yaquis joining the colonizers’ effort to subdue an Indigenous population, but according to the historian, Ignacio Lagarda, the Yaquis were always willing to fight an enemy but were unaware of the full situation among the Indigenous Moroccans. In the end the Yaquis who went also didn't really see a benefit as the late Anthropologist Raquel Padilla Ramos describes this event as yet another deportation effort to avoid another Yaqui conflict. Many Mexican officers returned to Mexico but with no Yaquis. Some Yaquis were left in Morocco and most likely integrated with the local communities.

Contemporary Yaquis

Tensions between the Yaquis and the Mexican government would continue as armed conflicts up to 1927, when peace was established. Then, in 1937, the Yaquis were given land under the presidency of Lázaro Cárdenas. On the U.S. side, many of the origin communities founded by the Yaquis in the late 19th and early 20th centuries would be abandoned or forgotten, but some like Tucson and Guadalupe continued to grow, which allowed the Yaquis in 1978 to establish the federally recognized Pascua Pueblo Yaqui Reservation near Tucson.

There have been multiple Yaqui organizations established in Southern California and Lubbock, Texas, to promote Yaqui culture. Today images of the Yaqui culture are honored throughout the state of Sonora, such as the Yaqui Deer Dancer Statue that measures at 33 meters tall at Loma de Guamuchil, north of Ciudad Obregón. There are over 20,000 Yaquis living in both countries, where most of them continue their traditions.

Modern Mexican Disporas

Today many descendants of Native Mexicans live throughout the world. The United States of America has the largest number of Mexican descendants with about 37 million. This large number is due to multiple reasons: First, the U.S. acquired much of their modern western states from Mexico at the end of the Mexican-American War and Gadsden Purchase. Second, the demand for labor was filled by Mexicans who helped transform the USA in various industries. However, Mexican migration in the United States has slowed down since the economic crash of 2008. Other countries with over 20,000 Mexican descendants include 155,000 in Canada; 61,000 in Spain; 41,000 in Germany; 40,000 in France; and 25,000 in Brazil. The Mexican diaspora is also not limited to planet earth as Rodolfo Neri Vela was the first Mexican to travel to space with NASA in 1985. Following him would be six additional Mexican-Americans who went beyond earth's surface. With them came the Mexican symbols of tortillas, the Virgen de Guadalupe, and the Mexican Flag which all traces back to the Indigenous ancestry of Mexico.

References:

Amezcua, Everardo Suárez. “II. Combatientes Yaquis En El Norte de África: Asociación de Diplomáticos Escritores.” Asociación de Diplomáticos Escritores • Diplomacia, desarrollo, paz, January 16, 2018. https://www.diplomaticosescritores.org/article/ii-combatientes-yaquis-norte-africa/

Chipman, Donald E. Moctezuma’s children: Aztec royalty under Spanish rule, 1520-1700. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2021.

Cushner, Nicholas P. Legazpi 1564-1572 Philippine Studies, APRIL 1965, Vol. 13, No. 2 (APRIL 1965), pp. 163-206 Published by: Ateneo de Manila University Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/42720592

Escalante Arce, Pedro. Los Tlaxcaltecas en Centro América. El Salvador: Concultura. Dirección de Publicaciones e Impresos, 2004.

Gibson, Charles Tlaxcala in the Sixteenth Century. Stanford, Stanford Press. 1967.

Gonzalez Acosta, Alejandro. .Migraciones Tlaxaltecas hacia centro y Sudamerica la otra frontera El Sur. Revista de Historia de América No 129 pp. 103-144 July-December 2001. Pan American Institute of Geography and History https://www.jstor.org/stable/44732856JSTOR

Hassig, Ross. Aztec warfare: Imperial expansion and Political Control. Norman, Okla: University of Oklahoma Press, 1995.

Matthew, Laura E, Oudijk, Michel R. Indian Conquistadors Indigenous Allies in the Conquest of Mesoamerica . Norman. University of Oklahoma Press, 2007

Reff, Daniel T. Disease, Depopulation and Culture Change in Northwestern New Spain, 1518-1764. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1991.

Regalado Pinedo, Aristarco. “. El Ejército de Nuño Beltrán de Guzmán.” Estudios Militares Mexicanos , Guadalajara Universidad de Guadalajara, , xi 2021. 17–40.

Rodriguez, Jonathan. “The Indigenous Legacy of Sinaloa.” Indigenous Mexico, January 11, 2025. https://www.indigenousmexico.org/articles/the-indigenous-legacy-of-sinaloa.

Schmal, John. “The Tlaxcalan Migrations to Northern Mexico.” Indigenous Mexico, September 4, 2024. https://www.indigenousmexico.org/articles/the-tlaxcalan-migrations-to-northern-mexico.

Spicer, Edward H. “The Yaquis: A Cultural History” Tucson, University of Arizona Press: 1980.