Nine Generations of Californians: Serving Under Three Flags

The state of California is a very special place for many people. Millions have come here from other parts of the United States and from around the world to live, work, and prosper. And many of these people embrace their new lives in this western state. California is also an economic powerhouse. Today, if California were a nation, it would rank as the fourth largest economy in the world, behind Germany and ahead of Japan.

One Family’s Dedication to California

Several families that came to California in the 18th Century have specialized in defending this state against all foreign threats (even before it was a state). One such family are the descendants of Juan Matias Olivas, who came to California with his family in the Expedition of 1781 [which will be discussed below]. Juan Matias Olivfas and his descendants had dozens of family members who have served in the California military for over two centuries. This article will discuss 14 of those individuals who served from 1781 to 1985. Three of these individuals died while in the service (two of them were killed in action). This article pays tribute to their service to California. Over a period of two centuries, the flags, the causes, and the surnames have changed, but the Olivas family's legacy of military service to California has endured.

Juan Matias Olivas Comes to California in 1781

In 1781, when an expedition was organized to bring a small group of civilian settlers from Sonora, Mexico to take part in the founding of El Pueblo de Nuestra la Reina de Los Angeles del Rio Porcioncula, an escort of several dozen Mexican soldiers serving under the flag of Spain were recruited. One of those soldier recruits was Juan Matias Olivas, a mulato libre from Rosario, Sinaloa. Although he didn’t realize it at the time, Juan Matias OIivas and his wife would be the progenitors of a large family that served in the military, defending California against all invaders for the better part of two centuries. One member of this family, the late Simon Melendez, a hero of the Korean War, once said to other family members, “Our family has known no home but California.”

The Olivas family’s long, proud tradition of military service began with Juan Matias Olivas, but it did not end there. One generation after another joined the military to defend their homeland. From the first moment Juan Matias Olivas entered California – and for the better part of at least nine generations – this family has played a role in defending California.

Juan Matias Olivas: The Progenitor

Juan Matias Olivas was born about two and a three-quarters centuries ago near Rosario in what is today known as the state of Sinaloa (in the Republic of Mexico). Although several Olivas individuals were born in Rosario in the mid-18th Century, Juan Matias’ baptism has not been located. Rosario, Sinaloa is about 1,060 miles southeast of Los Angeles.

In a life that lasted slightly less than fifty years, Juan Matias was married in 1777 (in Rosario, Sinaloa) and in 1799 (at the San Gabriel Mission). Through his two wives, he is believed to have had a total of eleven children (five in the first marriage and six in the second marriage). Eight of those children lived to become adults.

The Marriage of Juan Matias Olivas (1777)

On May 25, 1777, Juan was married at Nuestra Señora del Rosario Church in Rosario to María Dorotea Espinosa, and a portion of that marriage record is shown below:

The Marriage of Juan Matias Olivas and Maria Dorotea Espinosa (1777).

The May 25, 1777 marriage of Juan Matias Olivas and Marta Dorotea Espinosa took place in Rosario in southern Sinaloa. Juan Matias Olivas was described as a mulato libre originally from Matatan whose parents were not known [padres no conocidos]. According to his military discharge papers, he was the son of Francisco Olivas and Maria Goralsa. Juan Matias’ bride, Maria Dorothea Espinosa, was originally from the Villa of San Sebastian and she had been a maid (criada). Her parents’ names were also unknown. Matatan is about nine miles from Rosario. The document can be accessed in Rosario Marriage FHL Microfilm 676111, Image 21 of 536.

Three years later, their second child, José Pablo Olivas, was born on January 25, 1780. According to his baptism – which has been reproduced below – Jose Pablo was classified as a mulato and as the legitimate son of the legitimate marriage of Juan de Olibas [Olivas] and Dorothea Espinosa. The baptism of Jose Pablo has been reproduced below:

The Baptism of Jose Pablo Olivas (1780). Source: FHL Microfilm #677405, page 130, Image 443 of 696.

Juan Matias Olivas Enlists as a Soldier (1780)

On August 6, 1780, Juan Matias Olivas, enlisted for ten years as a soldado de cuera (leather-jacket soldier), attached to the Military District of Monterrey of Northern Mexico. Juan Matias' discharge papers of 1798 – reproduced below – state that Juan Matias de Olivas was the son of Francisco [Olivas] and Maria Goralsa and a native of the Real de Rosario. He was a farmer by trade at the time of his recruitment. We also learned about his physical traits. He was 22 years of age and had a height of 5 feet and 2 inches. He had black hair and black eyes. In addition, Juan Matias had olive skin and - unlike many of his fellow soldiers - was clean-shaven, an obvious manifestation of his predominant Native American ancestry (at a time when many men and soldiers had facial hair).

Juan Matias Olivas Military Discharge Papers (1798).

Joining Spain's frontier army offered Juan and his family with great opportunities that were not available to non-Spanish individuals (Indians, mestizos and mulatos) who lived in the Rosario area. If he had stayed in Rosario, Juan Matias Olivas would have been destined to a life as a poor Indigenous farmer subject to the whims of his hacienda jefe and to a society that classified him within the lower rungs of its racist caste system.

But, as a soldier serving in the Spanish military, Juan Matias would be permitted to ride a horse, carry his own weapon, have access to skilled medical attention, and enjoy free housing. Such a profession also provided him with retirement benefits and guaranteed that his wife would receive a pension if he died while performing his duties.

The Expedition of 1781

At about this time, Captain Fernando Rivera was scouring the coastal cities of Sinaloa and Sonora to find and recruit 59 soldiers and 24 families of pobladores (settlers) who would make up the nucleus of an important expedition to the north. The ultimate goal of the expedition would be the founding of the Pueblo of Los Angeles and the Military Presidio of Santa Barbara. In the end, Rivera was only able to recruit twelve families, which would be accompanied by 59 soldiers on the northward journey. In addition to recruiting soldiers and settlers, Rivera had to purchase equipment and supplies, as well as 961 horses, mules, and donkeys.

Upon completion of his recruitment task, Rivera’s entire expedition of settlers, soldiers, and livestock were assembled at Álamos in January 1781. From Álamos, the recruits and their families would move on either by sea or land in two separate groups. The following map by Phil Townsend Hanna, in the “Ruiz Genealogy” shows the two routes from Alamos, Sonora to San Gabriel, California, one in red and one in green.

The Two Legs of the Expedition of 1781.

In April 1781, Captain Rivera led 42 soldiers and 30 families up the long, arduous overland route through desert brush and hostile Indian territory. Progress was quite slow, in accordance with their directive, to avoid needless fatigue and hardship to the families, and to keep the livestock in good condition.

A list of the soldiers and families that took part in the Expedition of 1781 can be seen in Thomas Workman Temple II, “Soldiers and Settlers of the Expedition of 1781,” Southern California Quarterly, Vol. XV, Part 1 (November 1931), which can be accessed on FHL Microfilm 1548299, starting at Image 918 at the following URL:

https://www.familysearch.org/ark:/61903/3:1:33S7-9TWQ-HNM

A more detailed discussion of the Expedition of 1781 and some of the people who took part on the expedition can be seen at this link:

https://drive.google.com/file/d/1H7a1zhAkaAiCa3lJt6Io2qCAXkhM2s_s/view

Rivera’s Forces Are Attacked (July 1781)

Captain Rivera and his troops arrived in July at the junction of the Gila and Colorado Rivers. At that point, Rivera sent the troops and their families – including Juan Matias Olivas and his family – ahead to the San Gabriel Mission. With several men still under his command, Rivera camped on the eastern (Arizona) bank of the Colorado River on the night of July 17, 1781 in order to rest and feed his livestock before crossing the Colorado Desert.

However, Rivera’s large herd of cattle and horses caused a great deal of damage to the mesquite trees and melon patches of the Indigenous inhabitants of the area. Enraged, the Yuma Indians (now known as Quechan) attacked and massacred Rivera and several of his soldiers. The Indigenous inhabitants also attacked other nearby pueblos, killing many people. This massacre caused a great deal of trepidation to the Spanish frontier zone. As a result, the inland route from Sonora to California was virtually closed for several years. But Juan Matias Olivas and his family were able to arrive in San Gabriel, where they stayed for about half a year.

The Pueblo of Los Angeles Is Established (September 1781)

In the months following their arrival at the San Gabriel Mission, Juan Matias Olivas and his family were housed with the rest of the soldier families near the mission. Soon after, on the morning of September 4, 1781, the Pueblo of Los Angeles was founded, with forty-four settlers and several soldiers in attendance. It is likely that the services of several soldiers - including Juan Matias Olivas - were needed to help the small pueblo get started. Juan Matias, as a matter of fact, would - after his enlistment ended - make his retirement home in the small pueblo.

The Olivas Family Moves on to Santa Barbara (1782)

Early in the next year, Juan Matias Olivas and forty-one other soldiers made their way to the Santa Barbara Channel, where, on April 21, 1782, the Santa Barbara Presidio was founded. Not long after, the families followed, and the rest of his military career would be spent at the Santa Barbara Presidio.

The Responsibilities of a Presidio Soldier

As a Presidio soldier, Juan Matias Olivas and the other soldiers had a multitude of responsibilities: Sometimes they delivered the mail to other parts of California or escorted priests to and from their destinations. A regular escort of fifteen soldiers from Santa Barbara were posted to guard the San Buenaventura Mission. And, of course, there was always the possibility that they would be called upon to take part in an Indian campaign. (The soldados posted in New Mexico, Arizona, Texas and Chihuahua were almost constantly at war with the indigenous groups. By comparison, the Santa Barbara area was relatively calm, and the Spaniards cultivated their relationships with most of the Indian groups surrounding their presidios. The rebellions would come later.)

A look at the July 1, 1784 “Disbursement of [the Santa Barbara] Presidio,” as compiled by Captain Goycoechea, provides us with a good example of the many duties of presidial soldiers. The summary showed the activities of the sixty officers and men who were stationed at the presidio on that day:

“Disbursement of [the Santa Barbara] Presidio” Signed by Captain Felipe de Goycoechea, July 1, 1784 From the Archivo General de la Nación, Obras Públicas, Tomo 15.

The Olivas Family in the 1785 Census

In the first complete census taken at the Real Presidio de Santa Barbara on December 31, 1785, Juan Matias was listed as a 26-year-old mestizo. The census listed his wife, M. Dorotea Olivas, as a 27-year-old mestiza. They had three children. On September 9, 1789, Juan Matias’ wife, Dorotea, died, leaving poor Juan Matias a widower with six children: Nicolasa, Pablo, Cosme, Juana, José Delores and Madeline.

The Olivas Family in the 1790 Census

Not long after he was widowed, Juan Matias Olivas was tallied in the 1790 census of the Real Presidio de Santa Barbara [Provincial State Papers, Benicia Military, XIII, 448-454]. Listed as a 31-year-old widower, Juan was classified was a mestizo and a native of Rosario [Sinaloa]. Four of his six children were listed with their respective ages: María Nicolasa (11 ½); Juan Pablo (9 ½); Cosme (6); and María de Los Santos (2). By now, the entire population of the Santa Barbara Presidio had reached 230 individuals, comprising 24 percent of the entire Hispanic population of Alta California.

A State of War Exists (1794)

In March 1794, Spain declared war against France. Eventually the news of this war arrived in California. The soldiers became acutely aware of the fact that both France and England yearned for the opportunity to take California into their own empires. But it was not likely that the two hundred and seventy-five soldiers at the four presidios in California could have held off a serious invasion by a foreign power. Nevertheless, the presidio was their home, and steps were taken to safeguard the safety of their families and possessions in case of attack. On June 1, 1794, Juan Matias married his second wife, Juana de Dios Ontiveros, at the San Gabriel Mission. After their marriage, Matias and Juana had a son named José Herculano. Two years later, another son, Lazaro, was born, but lived only four months.

Juan Matias Olivas Retires to Los Angeles (1798)

On November 23, 1798, Felipe de Goycoechea, the Captain of the Santa Barbara Presidio submitted a list of nine soldiers who deserved to be designated as “invalid soldiers.” Forty-year-old Juan Olivas was one of the soldiers listed. He had served 18 years in the military and was described as “languid and ailing.” His intended home was the Pueblo of Los Angeles, which had become a retirement settlement for many of the soldiers from the Santa Barbara Presidio [Simancas, Legajo 7029, Expediente 1, Pages 126-136]. Within two years, Juan Matias Olivas and his family had taken up residence in the small pueblo of Los Angeles. By this time, the small pueblo had seventy families, 315 people, and consisted of thirty small adobe houses.

In 1804, Juan Olivas was listed in the Los Angeles “Easter List” Census as a retired soldier. Living with him were his wife, Juana Ontiveros, and their children: Cosme, María, and Juana Olivas, and Pedro Ontiveros [The 1804 Easter List is in William M. Mason, Los Angeles Under the Spanish Flag (Burbank, Southern California Genealogical Society, 2004), pp. 77, 85]. Juan was given lands which he was cultivated until his death in 1806. His burial record at San Gabriel Mission [Burial Record #2703] indicated that he was buried on December 2, 1806.

The Second Generation: Jose Pablo Olivas

José Pablo Olivas was the son of Juan Matias and Dorotea, As stated earlier, he had been born in Rosario, Sinaloa, on January 25, 1780 as the legitimate son of Juan Matias Olivas and Dorothea Espinosa. Listed as a mulato in the church’s baptism records, José Pablo was baptized on February 20 with Manual Theodoro Cillas and María Paula Cillas as his godparents. José Pablo was the second child of the young couple, Juan Matias and Dorothea.

But, from the age of two, Pablo grew up within the walls of the Santa Barbara Presidio. Living at close quarters with fifty other families was no easy chore, but the inhabitants of the garrison were united in their camaraderie as the families of soldiers. As a child, José Pablo attended the same church services at the Santa Barbara Mission as his future wife, María Luciana Fernández, the first-born child of another presidial soldier, José Rosalino Fernández. Their 1800 marriage record at the Santa Barbara Mission has been reproduced below.

The Marriage of Jose Pablo Olivas and Maria Luciana Fernandez, January 7, 1800 [Santa Barbara Presidio Marriage #42].

A partial translation of Santa Barbara Presidio Marriage #34 on January 7, 1800 reads as follows:

On the 7th day of the month of January of the Year of Our Lord of 1800, in the Church of this Mission of Santa Barbara, having made the proper presentation, the due information, and having read the three canonical admonitions on three festive days, without any impediment whatsoever, I married in the face of the church, by the words of those present… JOSEF PABLO OLIVAS, single, originally from Rosario, Sinaloa, and a soldier of the Real Presidio de Santa Barbara, the legitimate son of Juan Matias Olibas and Maria Dorothea Barbara Espinosa, both from the aforementioned Rosario, and [now] residing in the Pueblo of the Queen of Los Angeles, with MARIA LUCIANA FERNANDEZ, originally from the Presidio of Santa Barbara, single, and the legitimate daughter of Josef Rosalino Fernandez, originally from the Villa del Fuerte and resident of San Blas, and of Juana Quinteros from the Real de Los Alamos and a resident of this Presidio of Santa Barbara…

Between 1801 and 1812, José Pablo and María Luciana would have eight children, including José Dolores de Jesus Olivas, who was baptized on Nov. 3, 1802 at Santa Barbara, and would represent the third generation of Olivas soldiers.

Jose Pablo Olivas Becomes a Soldier

Shortly before 1800, José Pablo Olivas stepped into his father's footsteps and became a soldier of the Santa Barbara Presidio. In a roster of individuals dated February 17, 1804, Pablo Olivas was listed as one of the fifty-four soldiers on active duty at the Santa Barbara Presidio.

The Mexican War of Independence (1810-1821)

Mexico's struggle for independence against Spain began on the night of September 15/16, 1810 when a mild-mannered Creole priest, Father Miguel de Hidalgo y Castillo, published his famous outcry against tyranny from his parish in the village of Dolores. His impassioned speech - referred to as Grito de Hidalgo ("Cry of Hidalgo") - set into motion a process that would not end until August 24, 1821 with the signing of the Treaty of Córdova.

From 1810 through 1821, Mexico's war of liberation interfered with the arrival of Spanish supply ships in California. Eventually, supplies dwindled to a mere trickle, making the California presidios more dependent upon the local missions for food supplies and manufactured items. By 1813, the Commandant of Santa Barbara informed the Governor that his soldiers were without shirts and had little food; in addition, the presidio soldiers received no pay for three years, and pensions were suspended.

The Death of Jose Pablo Olivas (1817)

Four years later, on December 16, 1817, José Pablo Olivas, the second-generation soldier of California, died at the age of 37 years. According to Santa Barbara Burial #192, Pablo Olivas, a soldier of the Santa Barbara Company and the spouse of Maria Luciana Fernandez, died and was buried in the local cemetery. This document has been reproduced below:

The Burial Record of Pablo Olivas, December 16, 1817 [Santa Barbara Presidio Burial #192].

The Third Generation: Jose Dolores Olivas

José Pablo died when his son José Dolores Olivas was only fifteen years of age. It was during this period of intense upheaval that José Dolores Olivas stepped into his father's shoes and served as a third-generation soldado de cuera. José Dolores Olivas would become the third generation of Olivas men to become a soldado de cuera at the Santa Barbara Presidio. It was his destiny to see the transition of California as it passed from the hands of the Spanish empire to the newly independent Mexican Republic. And he would serve as a soldier to both nations.

In 1821, Mexico had finally achieved independence from Spain, and on April 1822, the California soldiers were notified the revolt had been successful. Almost immediately, the California presidios lowered the Spanish flag, and Alta California became part of the new nation of Mexico. On April 13, 1822, José Dolores Olivas and the other soldiers at the Santa Barbara Presidio took their oath of allegiance to the new government in Mexico City.

The Marriage of Jose Dolores OIivas and Gertrudes Valenzuela (1829)

On June 14, 1829, José Dolores de Jesus Olivas was married to María Gertrudis Valenzuela at Mission Santa Ynez [Santa Ynez Mission Marriage #386]. Dolores Olivas was listed as a single soldado de cuera and a native of the Santa Barbara. His bride, Gertrudis, was a daughter of another presidio soldier, Antonio Maria Valenzuela and his wife, María Antonia Feliz. María Gertrudis Valenzuela had been baptized sixteen years earlier on June 7, 1813 at the San Gabriel Mission. Like her husband, she was the daughter of a presidial soldier and had spent her early years growing up at the presidio. The marriage record has been reproduced below:

The Marriage of jose Dolores de Jesus Olivas and Maria Gertrudis Valenzuela, Jun 14, 1829 [Santa Ynez Mission Marriage #386].

The Family of Jose Dolores Olivas

As José Dolores and Gertrudis prepared to start their family in 1830, they took their position as members of the growing Santa Barbara presidial community, which now numbered 604. Between 1830 and 1850, José Dolores and Gertrudis became the parents of twelve children.

The children of José Delores and María Gertrudis, with their approximate dates of baptism at the Santa Barbara or San Luis Obispo missions, are listed as follows: 1) José Antonio Santiago (April 1830); 2) Juana de Dios (March 1832); 3) María Antonia Blanca (February 1834); 4) Susanna Blanca (February 1834); 5) Apolinario Guillermo (September 1836); 6) María Eulalia (November 21, 1839); 7) José Ignacio Antonio Victoriano (circa 1840); 8) Mariana Silveria (June 9, 1841); 9) Carolina Celestina (June 1843); 10) Blas Felipe (February 3, 1846); 11) José de los Santos (April 18, 1848); and 12) Nicolas Amado (September 13, 1850). Two of the sons — Victoriano and Blas Felipe — would become soldiers and take part in the American Civil War. María Antonia Olivas, born in February 1834, would be the ancestor of several soldiers that would take part in the Twentieth Century wars of the U.S.

After serving out his term of enlistment, Dolores Olivas retired from the military and became an agricultural laborer. He and his family continued to live in the vicinity of the presidio. It was during this time that President James K. Polk of the United States devised a strategy for snatching California from the hands of the Mexican Republic.

The Mexican American War (1846-1847)

In the fall of 1845, President Polk sent his representative John Slidell to Mexico. Slidell was supposed to offer Mexico $25,000,000 to accept the Rio Grande boundary with Texas and to sell New Mexico, Arizona, and California to the U.S. However, the President of Mexico turned this down, and in May 1846 Polk led his country into war. The Mexican-American War in California ended on January 13, 1847 with the signing of the Treaty of Cahuenga.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848)

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed on February 2, 1848, ending all hostilities between the two nations. By the provisions of this treaty, Mexico handed over to the United States 525,000 square miles of land, almost half of her national territory. In compensation, the U.S. paid $15,000,000 for the land and met other financial obligations to Mexico. By the provisions of this peace treaty, the Mexican citizens living in California were offered American citizenship and full protection of the law. The area which Mexico transferred to American control in 1848 contained a population of 82,500 Mexican citizens, 7,500 of which lived in California. Two years later, on September 9, 1850, California was admitted to the Union as the thirty-first state.

The Dolores Olivas Family in the 1850 Census

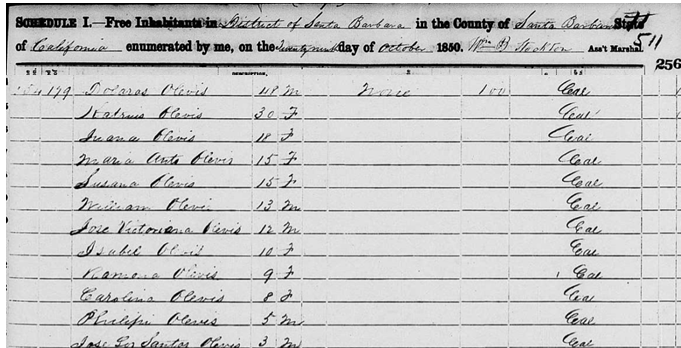

During the Federal Census of the same year,49-year-old Dolores Olivas - now an American citizen - was tallied in his Santa Barbara residence as the head of a household of eleven on October 29, 1850. His occupation was not listed, but he owned real estate valued at $100 [1850 United States Federal Census, District of Santa Barbara, Santa Barbara County, California, Page 256, Dwelling #154, Family #179]. As noted in the following census, his wife Gertrudes was erroneously written down as Katrina Olivas. Together, they had 10 children ranging in age from 18 years to 3 years.

The Olivas Family in the 1850 Federal Census.

The Dolores Olivas Family in the 1852 California Census

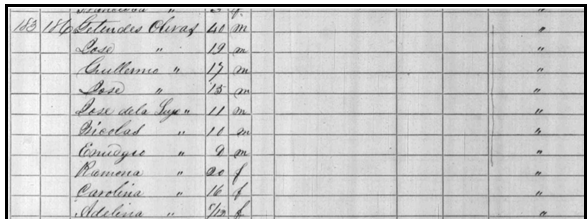

In the 1852 California Census, Dolores Olivas was listed as 56 years of age. [He was actually only 50 years old.] His wife, Gertrudes Valenzuela de Olivas, was 40 years old and they had a large, extended family that included 8-year-old Jose Olivas and 6-year-old Felipe Olivas. The family lived in Santa Barbara County and the Dolores Olivas family is shown as follows:

The Extended Dolores Olivas Family in the 1852 California Census.

The Fourth Generation of the Olivas Family

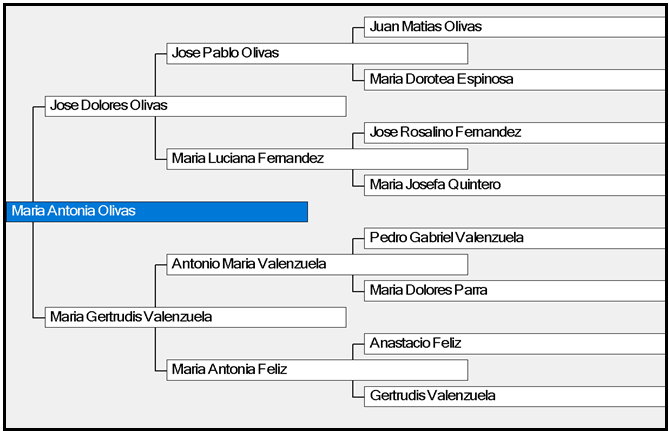

At the time of the 1850 census, one of the older daughters of Dolores and Gertrudes was 15-year-old María Antonia Olivas. She was truly a daughter of the Californian military establishment. She was descended from five pioneer California families (Olivas, Fernández, Valenzuela, Feliz and Quintero) and lived at the Santa Barbara Presidio which four of her soldado ancestors had helped to establish. Her father (José Dolores Olivas) was a retired soldier. Both of her grandfathers were California soldiers (José Pablo Olivas and Antonio María Valenzuela), as were all four of her great-grandfathers (Juan Matias Olivas, José Rosalino Fernandez, Pedro Gabriel Valenzuela, and Anastacio María Feliz). Maria Antonia Olivas would also be the ancestor of several family members who went to war to defend California and America in World War II and the Korean War.

A Military Family of California

The father, the grandfathers, and the great-grandfathers of Maria Antonia Olivas were all members of California’s military from the 1770s to the day of her birth in 1834. Her ancestral forebearers are illustrated in the following chart. This was not very unusual for the children of soldiers who grew up in presidios and then married the child of another soldier.

The Ancestors of Maria Antonia Olivas [A Four-Generation Chart].

The Family of Maria Antonia Olivas

On November 30, 1849, María Antonia Olivas was married to José Apolinario Esquivel, a native of Irapuato, Guanajuato, Mexico, at the Santa Barbara Mission. The two of them relocated to the San Buenaventura Township to raise their family and tend their crops. They raised a big family and many of their descendants would serve in the United States Army.

The Olivas Family in the 1860 Federal Census

Dolores Olivas is believed to have died in 1860. Shortly afterward, his widow 40-year-old Gertrudes Valenzuela was tallied in the 1860 census with five of her children [ranging in age from 19 to 10 years of age], as well as other relations. The census has been reproduced below [Family 186, 1860 Federal Census, Santa Barbara Township, Santa Barbara County, California, Page 28.]

The Olivas Family in the 1860 Census.

The American Civil War (1861-1865)

The American Civil War (1861-1865) divided the American people into two camps and resulted in more casualties than any other war in American history. Many of the hostilities in this war took place in the eastern half of North America, especially in the Southern states. For the most part, California — which was a Union state — seemed removed from most of the battlefield action that was taking place.

Creation of First California Native Cavalry (1863)

In 1863, as the Civil War raged in the eastern and southern states, the United States Government became concerned about possible Confederate incursions into New Mexico and other Union-held areas. In order to avoid such confrontations, the U.S. Government authorized the military governor of California to organize four military companies of Mexican American Californians into a cavalry battalion in order to utilize their "extraordinary horsemanship."

There is a detailed discussion of the Native Cavalry at the following link: Tom Prezelski, “California and the Civil War: 1st Battalion of Native Cavalry, California Volunteers” (Jan. 25, 2005). Online:

https://www.militarymuseum.org/1stNatCavCV.html

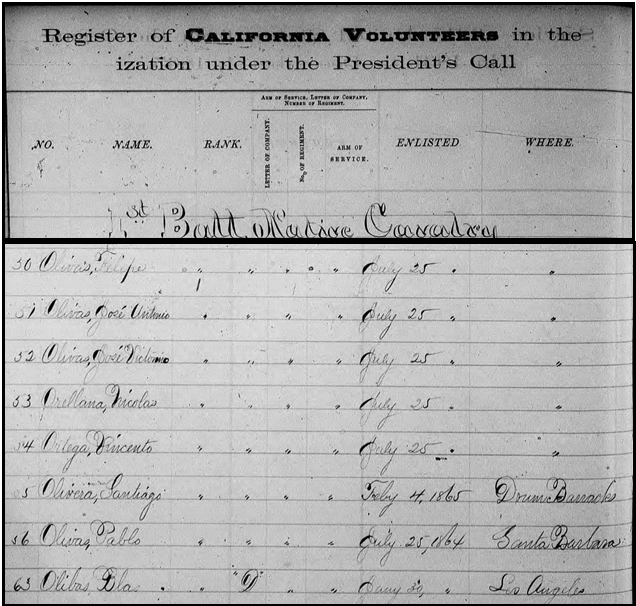

Major Salvador Vallejo was selected to command this new California militia, with its five hundred soldiers of Spanish and Mexican descent. Company C of the First California Native Cavalry was organized under Captain Antonio María de la Guerra. The following members of the Olivas family would take part in this endeavor.

José Victoriano Olivas

The younger brother Maria Antonia Olivas, José Victoriano Olivas enlisted on July 25, 1864 at Santa Barbara as a private in Company C and mustered in the next day. At his enlistment, he was described as age 23, height 5 feet 7 inches, with a dark complexion, as well as black eyes and hair. He had been born in 1841 as the son of Dolores Olivas and Gertrudes Valenzuela. He was a ranchero by trade.

José Victoriano Olivas’s battalion primarily served in California and Arizona, guarding supply trains and safeguarding Union territory against a possible Confederate invasion. José Victoriano Olivas would thus become part of the fourth generation of the Olivas family to serve in the military. And this service had now been extended to three flags (Spain, Mexico, and the United States). Private Olivas mustered out at Presidio San Francisco on April 2, 1866.

Félipe Olivas

Blas Félipe Olivas, another brother of Maria Antonia Olivas, enlisted on June 25, 1864 and was mustered in at Santa Bárbara as Private of Company C three days later. Félipe Olivas was the son of Dolores Olivas and had been born about 1845 at the Santa Barbara Mission. At his enlistment, he was described as 20 years of age, with a height of 5 feet, 7 inches. He had a dark complexion, as well as black eyes and hair. He would be mustered out at the Presidio of San Francisco on April 2, 1866.

Blas Olivas

Blas Olivas enlisted at Los Angeles January 30, 1864 as a private in Company D. He had been born in 1836 and baptized at Santa Barbara Mission as the fifth son of the sixteen children of Juan Silvestre Olivas and Clara Pico. Silvestre Olivas was born in 1806 as the son of Pablo Olivas and as the younger brother of Jose Dolores Olivas. Therefore, Blas and Victoriano were first cousins.

He was mustered into the service on March 3, 1864. At his enlistment, he was described as 26 years of age, his height was 5 feet, 10 inches, and he had a dark complexion, with black eyes and hair. His birthplace was recorded as Santa Bárbara and his occupation was described as “vaquero.” Private Olivas mustered out at Drum Barracks on March 20, 1866.

José Antonio Olivas

José Antonio Olivas enlisted and was mustered in at Santa Barbara as a private of Company C on July 25, 1864. At his enlistment, he was described as having a height of 5 feet, 9½ inches. He also had a dark complexion, as well as black eyes and hair. He was born as Juan Antonio Olivas in 1844 and was the son of Luis Olivas and Isabel Valenzuela. Luis Olivas was the son of Pablo Olivas and the brother of Dolores Olivas. This also made Antonio Olivas a first cousin to Victoriano Olivas.

Jose Pablo Olivas

Jose Pablo Olivas enlisted as a private in Company C at Santa Barbara on July 25, 1864. He was mustered in on the same day. Like Jose Antonio Olivas, he was a son of Luis Olivas and Isabel Valenzuela, born in 1842. He died of consumption [tuberculosis] at Drum Barricks on December 26, 1864.

All five Oiivas soldiers were shown in a Register of California Volunteers [California Adjutant General’s Office, California Military Records in the State Archives, 1858-1923, FHL Microfilm #981533, Enlisted Men, 1861-1865, page 103, Image 107 of 499 from Ancestry.com [Accessed 5/4/2025]].

The Olivas Soldiers in the Civil War.

The veterans of the Santa Barbara company were welcomed home with a parade down the dusty lane that would become State Street and by a two-day fiesta in De La Guerra Plaza. The events of the Civil War and their political fallout had given the old families of Spanish California power and prestige that they had not enjoyed since the American conquest. For a short time, the service of these California vaqueros-turned-cavalrymen gave the Californios of Santa Barbara a chance to celebrate and pay tribute to their military service.

The Fifth Generation: Regina Esquivel

Regina Esquivel was born in 1851 as the daughter of José Apolinario Esquivel and María Antonia Olivas. She was one of the first members of her family to be born an American citizen. Nineteen years later, on January 3, 1870, Father Juan Comapla joined Regina Esquivel in marriage with Gregorio Ortega at the San Buenaventura Mission [Certificate of Marriage, Ventura County Recorder’s Office, filed for record, January 31, 1870]. Gregorio Ortega was a laborer who had emigrated from southern Mexico in the 1860s. Over the next two decades, Gregorio and Regina would become the parents of eighteen children.

The Sixth Generation: Valentine Ortega

On September 16, 1875, Gregorio Ortega and Regina Esquivel became the parents of Valentine Ortega. Eighteen years later, Valentine was united in marriage with one 18-year-old Theodora Tapia, a native of the Los Angeles area. Valentine and Theodora had five children in all, including Isabel (born in 1902), Paz (born in 1906) and Luciano P. Ortega (born in 1908). During the early Twentieth Century, this family lived in the Saticoy District of Ventura County, California. Saticoy was nine miles east of the county seat, the City of Ventura.

With several children to take care of, Valentine Ortega did not serve in the American military when war came in 1916. However, he did register for the draft at the Ventura Draft Board on Sept. 12, 1918, two months before World War I ended. The draft registration card indicates that Valentine was born on Feb. 14, 1879 [an incorrect date] and that he lived in Saticoy, Ventura County, California. The draft record has been reproduced below:

The Draft Registration of Valentine Ortega (September 1918).

Victims of the Worldwide Flu Epidemic (1918)

In 1918, the worldwide flu epidemic reached Saticoy and would wreak havoc on the Ortega family. According to the Ventura Free Press of Nov. 15, 1918 (page 3), “Saticoy is said to be badly infested with the epidemic.” At that time, a sickness hit the Ortega family in West Saticoy. As a result, one son Felix Ortega, died on November 4. A married daughter, Severana Acuña, also died on November 4. And finally, on November 6, Valentine Ortega, at the age of 43, fell victim to the influenza epidemic that ravaged so many families on the American continent at the end of World War I.

The Seventh Generation: The Ortega’s

As Isabel Ortega and Luciano Ortega grew up, they witnessed what would eventually be called the First World War. Initially the war broke out in Europe and, it was not until three years later that America would join this conflict, with its declaration of war on Germany on April 6, 1917. During this war, the American military was rife with discrimination against Hispanic and African American soldiers. Soldiers with Spanish surnames or Spanish accents were sometimes the object of ridicule and relegated to menial jobs, while African Americans were segregated into separate units. Some Hispanic Americans who lacked English skills were sent to special training centers to improve their language proficiency so that they could be integrated into the mainstream army.

The Ortega and Melendez Families

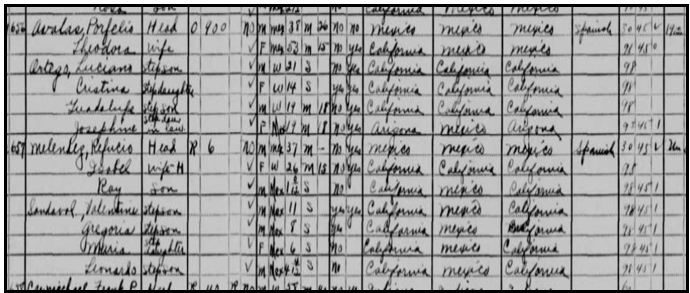

Luciano Ortega was born on January 7, 1908 in Camarillo as the son of Valentine Ortega and Theodora Tapia. After Valentine’s death, Theodora married Porfirio “Pilo” Avalos, an immigrant from Michoacán. In the 1930 census, Porfirio and Theodora lived on 4th Street in Ventura. At that time, Luciano Ortega was 21 years old and listed as a “stepson” to Porfirio. Two step-siblings and a step-sister-in-law lived with the family as noted in the following census schedules [1930 Federal Census, Saticoy, Ventura Township, Ventura County, California, Enumeration District 56-33, Sheet 39A].

The Avalos-Ortega-Melendez Households in the 1930 Census.

Isabel Ortega and Refugio Melendez

Living across the street from the Avalos-Ortega family was the household of Refugio and Isabel (Ortega) Melendez. Luciano’s sister, Isabel Ortega, had married Refugio Melendez, an immigrant laborer from Penjamo, Guanajuato. Refugio and Isabel met during the 1920s and their first-born child was Theodora (Dora) Melendez, who was born in November 1927. Dora was followed two years later by a son named Raymundo Melendez who was listed in the census as 1 year of age. Isabel and Refugio continued to raise their family in Saticoy for the next two decades, and eventually three of their sons would serve in the Korean War.

The Road to World War II

The Great Depression was a difficult time for the Melendez family as it was for most American families. But the beginning of World War II was an ominous event for all Americans. For three years, the United States avoided this war, which pitted the Axis Powers (Germany, Italy and Japan) against a multitude of other nations, including Great Britain, the Soviet Union, and China.

Pearl Harbor (1941)

On December 7, 1941, everything changed. The surprise attack on the American naval fleet at Pearl Harbor in Hawaii would bring America into this struggle against tyranny. And when Uncle Sam called for recruits, his call was answered. By the end of the war in September 1945, sixteen million men and women had worn the uniform of America's armed forces.

Mexican Americans Serving in World War II

At the time of America's entry into World War II (1941), approximately 2,690,000 Americans of Mexican ancestry lived in the United States. Eighty-five percent of this population lived in the five southwestern states (California, Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, and Colorado). Like other ethnic groups, Mexican Americans responded in great number to our nation's dilemma. At least 350,000 Chicanos served in the armed services and seventeen Hispanic individuals won the Congressional Medal of Honor. Some sources believe the number of Mexican Americans in the military exceeded 1/2 million.

California’s Role in World War II

California played an important role in World War II. Eighteen California National Guard Divisions were sent overseas, and thousands of men enlisted or were drafted. According to the United States War Department, California — containing 5.15% of the population of the United States — contributed 5.53% of the total number who entered the Army. Of these men and women from California who went to war, 3.09% failed to return home, representing 5.54% of the American casualties

Joseph Peregrino Ortega

Eventually, Luciano Ortega became known as Joseph Peregrino Ortega for reasons probably only known to his immediate family members. On November 10, 1931, the Ventura County Star (page 8) reported a notice of intention to wed for Joseph Peregrino Ortega, 28 years old from Saticoy, and Antonia Lopez, 18 years old from El Rio.

On October 16, 1940, year-old Joseph Peregrino Ortega appeared before the Local Draft Board in Santa Paula, California, to register for the draft. He stated that he was 31 years of age and was married to Mrs. Antonia Mary Ortega. At the time he worked on a ranch in Saticoy. His draft record has been reproduced below:

The Draft Record of Joseph Peregriano (Luciano) Ortega (1940).

In 1942, Luciano Ortega (aka Joseph P. Ortega) was drafted into the armed forces. According to the Ventura County Star of October 15, 1943 (page 10), Joseph P. Ortega, the son of Theodora Ortega of Saticoy, “ left for Fort McArthur at San Pedro to begin his army air forces ground crew training.” His date of enlistment was September 23, 1943. According to the enlistment records, Jose P. Ortega was attached to the 34th Infantry Regiment of the 24th Infantry Division, which would be on the front lines in the war against Japan. He soon went overseas to the “Eastern Theater” of the war.

The Death of Luciano Ortega (1944)

The 24th Infantry Division landed on Dutch New Guinea on April 22, 1944 and fought many battles over the next few months. Finally, on October 20, the 24th landed on Red Beach at Leyte, Philippine Islands. They engaged in very heavy fighting over the next month, taking Breakneck Ridge on Nov. 12th. On November 19, 1944, Luciano was killed in action. He was buried in the Manila American Cemetery in the capital city, Manila.

His mother, Theodora Tapia Ortega, never reconciled herself to her son's death and refused to accept it. Instead, she continued to believe that he was missing in action and would someday return home to Saticoy. According to the Ventura County Star [August 4, 1965, page 14], Theodora died 21 years later (in 1965) and was survived by four children, 38 grandchildren, 89 great-grandchildren and 15 great-great-grandchildren.

The Eighth Generation: Chello Ortega

The eighth generation of Olivas-Ortega family was involved in two wars: World War II and the Korean War. On April 19, 1943, 18-year-old Chello O. Ortega, the son of Paz Ortega (a sister of Luciano and Isabel Ortega) and Laurencio Ortega, registered for the draft at the Santa Paula Draft Board near Saticoy. According to his draft record, he had been born on April 15, 1925 and lived in Saticoy. His draft record has been reproduced below:

The Draft Record of Chello O. Ortega (1943).

At the time of his enlistment on January 20, 1944, Chello was a farm hand. Chello Ortega was the second Ortega to go to the Army from Saticoy and – like his uncle Luciano – was sent to the Pacific Theater. From the end of December 1944 through March 1945, Chello's unit prepared for the final campaign of the war: the invasion of Japanese territory. He was with the American troops that landed on Okinawa after the invasion began on April 1, 1945. The fighting was tough, and the Japanese fought for every inch of the island because this was the first time American troops were landing on true Japanese soil (as opposed to occupied territories).

Chello Ortega: Killed in Action

The Battle of Okinawa, codenamed Operation Iceberg, was the largest amphibious assault in the Pacific Theater of World War II and it lasted 82 days from early April until mid-June, 1945. Chello took part in the 383rd Infantry’s attack on Conical Hill and helped to defeat a Japanese counterattack on May 13th. However, he was killed in action the following day and a day later, on May 15th, the Deadeyes finally secured Conical Hill. According to the military report, Chello’s body was not identified until June 19th, five weeks after his death.

Initially, Chello was reported as “missing in action.” On June 27, 1945, a month-and-a-half after Nazi Germany had surrendered, the Oxnard Press Courier announced that Chello Ortega from Saticoy was missing in action in the Pacific Theater. Nine days later, on July 6, 1945, the same newspaper announced the sad news that Chello Ortega had been killed in action. Less than two months later, Japan would surrender, and peace would finally come to America after three years and nine months of war.

At first, Chello Ortega was buried at the Island Command Cemetery but his body was disinterred in November 1948 and returned for burial in Ventura County. His father waited at the train station for the body to be delivered so that he could arrange for a proper burial on Chello’s native California soil. On April 7, 1949, the Ventura County Star (page 2) reported that a rosary would be recited at the family home in Saticoy on April 8 for Chello O. Ortega. After his body’s return, funeral services were also conducted at the Saticoy Catholic Church on Saturday, April 9, 1949.

The Family of Refugio Melendez in the 1940 Census

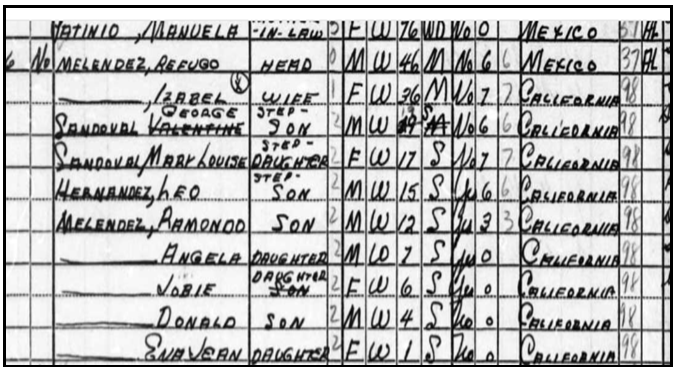

On April 11, 1940, the census taker arrived at the home of Refugio Melendez in Saticoy. At this time, 46-year-old Refugio Melendez had a household of ten that included his wife, 36-year-old Izabel, three step children and five children named Melendez. The children included 12-year-old Ramonod [Raymond] and 4-year-old Donald, who would eventually join the Army in the 1950s. The census schedules have been reproduced below [1940 Federal Census, Saticoy, Ventura County, Enumeration District 56-60, Sheet 10A]:

The Melendez Family in the 1940 Federal Census.

The Eighth Generation: The Melendez Brothers

As World War II drew to an end in 1945, the three Melendez brothers - sons of Refugio Melendez and Isabel Ortega - were teenagers. Raymond (Raymundo) Ortega Melendez had been born in 1929 and yearned to join the military. On February 9, 1945, Ray Ortega signed up for the draft at the Santa Paula Processing Center, claiming that he was born on February 7, 1927 and 18 years of age. This draft card has been reproduced below:

The Draft Registration of Ray Ortega Melendez (1945).

The Eighth Generation: Raymond Melendez

In 1945, at the age of 17 - with his parents' permission - Ray entered the American armed forces. This would mark the beginning of a long military career, which would take him through the Korean and Vietnam Wars before his retirement in 1969. Ray Melendez started out as an airborne paratrooper.

The Korean War began in 1950, only five years after the end of World War II. The participation of Mexican Americans and other Hispanics in the Korean War was such that the Department of Defense publication, Hispanics in America's Defense (Collingdale, Pennsylvania: Diane Publishing Co., 1997), has paid tribute to their contribution: "The Korean Conflict saw many Hispanic Americans responding to the call of duty. They served with distinction in all of the services…. Many Mexican Americans from barrios in Los Angeles, San Antonio, Laredo, Phoenix, and Chicago saw fierce action in Korea. Fighting in almost every combat unit in Korea, they distinguished themselves through courage and bravery as they had in previous wars."

The Eighth Generation: Simon Melendez

Born on October 28, 1930, Simon Ortega Melendez was raised in Saticoy and attended Ventura Junior High School and Ventura City College. When the Korean War started, Simon joined the 2nd Division of the U.S. Army and became a machine gunner. It would be Simon's destiny to take part in two of the bloodiest battles of the Korean War.

Lost Behind Enemy Lines (1951)

The "Battle of Bloody Ridge" began in August 1951 and continued up until September 12, 1951. On August 27, Simon was hit in the neck and legs by mortar shrapnel and in the back by grenade fragments. At the same time, he was separated from his platoon. For seven days, he was behind enemy lines and disoriented by torrential rains that made his weapon inoperable.

The rain did not stop until the sixth day, and on the seventh day he was able to make his way into the area of the 9th U.S. Regiment. When asked how he managed to make his way through enemy lines for seven days, 21-year-old Simon explained that "my extreme faith in God brought me through." Soon after, Simon was once again in the thick of the fighting when his unit took part in the "Battle of Heartbreak Ridge," which lasted from September 13 to October 22, 1951. Simon took part in the two bloodiest battles of the Korean War: The Battle of Bloody Ridge and the Battle of Heartbreak Ridge.

Two Brothers Unite in Korea (1952)

On February 27, 1952, the Ventura County Star (page 11) featured an article called “Two Saticoy Brothers Reunited For Three-Day Visit in Korea.” The article reported that “Simon Melendez, 21, and brother Raymond, 23, held their impromptu family gathering when Ray wrangled a three-day pass to make the 100-mile trip.” By this time, Raymond, a paratrooper, had been in Korea for six months. He had entered the service six years earlier (1946). His brother Simon, a machine gunner, had been in the army for eight months and had been in Korea for seven months – and had already been wounded.

By the time he finished his service as a platoon sergeant with the U.S. Army 2nd Division, Simon Melendez had been awarded the Silver Star, the Bronze Star, and three Purple Hearts. He also founded the Mexican-American Korean War Veterans of Ventura County and became a life member of the Veterans of Foreign Wars and the American Legion. Simon Melendez, the proud Korean War veteran, died at the age of 71 on June 15, 2002, surrounded by a family that adored him. Even to this day, the memory of Simon Melendez remains strong for the family, in large part because he had a larger than life personality that endeared him to everyone.

Other family members were inspired by Simon’s example and followed him into the service as they came of age. On April 27, 1977 (page 4), The Enterprise Sun & News reported that Simon’s son, Richard R. Melendez joined the Air Force, starting a six-week transitional training at Lackland Air Force Base, Texas. Another son, Roy Melendez, enlisted in the U.S. Marines.

The Eighth Generation: Donald Melendez

Donald Ortega Melendez, who was born in 1936, entered the service in 1954 at the tail end of the Korean War. Like his brother Raymond, he initially joined the paratroopers. During his first stint overseas, Donald was assigned to the 9th Infantry Regiment of the 2nd Infantry division. He did three separate hitches overseas and was in the service during the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962. Donald spent 25 years in the military and achieved the rank of First Sergeant before he retired in 1979. His son, Daniel Melendez, followed in his father's step and served as a paratrooper from 1970 to 1982.

The Ninth Generation: Eusebio Javier Melendez Basulto

When he was twenty years old, Theodora Melendez’s son, Eusebio “Chevi” Javier Melendez Basulto followed in the family's military tradition by enlisting in the U.S. Army. Chavi was the nephew of the three Melendez brothers. According to Eusebio’s March 2016 obituary, Chevi “served with great pride as a Hercules Missile crewman in Military Intelligence with MOS (Military Occupational Specialty) Unit 406 ASA from 1974 to 1976, where he achieved the rank of Specialist, Fourth Class. He served overseas in Germany and received the National Defense Service Medal and Letters of Appreciation. Eusebio's military career lasted from 1973 to 1985, a total of 12 years, after which he became a chemist in the civilian world. Chevi was very proud of his service to his country, and considered his military service to be one of his greatest accomplishments.”

A Long-Term California Military Family

Many Californians have served in the military. In some cases, multiple generations served their country a period of decades. However, it is a rare family that can claim that its ancestors entered California in the service of the Spanish military. Not only did the Olivas-Ortega-Melendez family provide servces to California through nine generations, but it also served under three flags [Spain, Mexico, and the United States]. This is an honor reserved for very few families. This service continues to this day.

Recommended Reading:

California Archives. Provincial State Papers, 1767-1822. Archives of California, Bancroft Library, U.C. Berkeley.

Leon Campbell, “The First Californios – Presidial Society in Spanish California, 1769-1822,” Journal of the West, 11:4 (October, 1972).

Mason, William M. Los Angeles Under The Spanish Flag: Spain’s New World. Burbank, California: Southern California Genealogical Society, Inc., 2004.

Office of the Deputy Assistant Secretary of Defense for Military Manpower and Personnel Policy, U.S. Department of Defense. Hispanics in America's Defense. Collingdale, Pennsylvania: Diane Publishing Co., 1997.

Parks, Marion. “Instructions for the Recruital of Soldiers and Settlers for California – Expedition of 1781,” Southern California Quarterly, Vol. XV, Part II (1931), pp. 189-203.

Prezelski, Tom. “California and the Civil War: 1st Battalion of Native Cavalry, California Volunteers” (Jan. 25, 2005). Online: https://www.militarymuseum.org/1stNatCavCV.html

Vo, Jennifer Vo and Schmal, John P. A Mexican-American Family of California: In the Service of Three Flags. Maryland: Heritage Books, 2004.

Weber, Msgr. Francis J. Weber (ed.). Queen of the Missions: A Documentary History of Santa Barbara. Hong Kong: Libra Press, Limited, 1979.

Workman Temple II, Thomas. “Soldiers and Settlers of the Expedition of 1781,” Southern California Quarterly, Vol. XV, Part 1 (November 1931),

Whitehead, Robert S. Citadel on the Channel: The Royal Presidio of Santa Barbara: Its Founding and Construction, 1782-1798. Santa Barbara: Santa Barbara Trust for Historical Preservation, 1996.