The Santa Ynez Mission Indians: Their Struggle for Land

The Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians is a federally recognized Native American tribe. Many of the members of this group live on the Santa Ynez Reservation located in Santa Barbara County, near the cities of Solvang and Santa Ynez. According to federal sources, the Santa Ynez Reservation was established and officially recognized by the federal government on December 27, 1901. However, the members of the tribe were registered in the U.S. Indian census as early as 1894 and for nearly every year thereafter up to 1940. Today, the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians remains the only federally recognized Chumash tribe in the nation. The tribe is a self-governing sovereign nation and follows the laws set forth in its tribal constitution.

There are two ways of spelling the Mission’s name: Santa Ynez [used more often in the present day] and Santa Inés, which is the Spanish spelling that is used by the Mission to this day. Most historical works have used the latter spelling.

California’s Mission System

In 1769, the Spaniards created a mission and presidio at San Diego. Over the next 54 years, they established 21 missions along the coastal region of California, along with several military presidios to protect the missions. These missions would be used to secure a firm hold on their California territory, which was densely populated with a large diversity of indigenous peoples. The primary Spanish goal was to develop presidios and missions, by which they would attempt to convert the native peoples to Christianity and make them part of the Spanish Empire. The following map shows the missions in the southern part of Colonial California.

The Early Missions in Southern California.

Map Source: Daniel P. Faigan, “California Highways — Trails and Roads: El Camino Real.” Online: https://www.cahighways.org/elcamino.html.

The Chumash as a People

It is important to point out that the Chumash Indians were never organized as a unified nation and their “basic political unit” was the town or ranchería they lived in or came from. In the baptisms and marriages of the six California missions where the Chumash lived, the missionaries referred to the rancherías they were born in or that they lived in. The various rancherías shared common cultural and linguistic features and were sometimes organized into federations.

The Early Chumash

No one knows for sure when the Chumash came to the Santa Barbara area. As early as 13,000 years ago, it is possible that an early Native American people may have lived in small groups, collecting shellfish and harvesting wild seeds. The climate was very cool and moist at that time but became warmer and drier around 6,500 years ago.

About 5,000 years ago, the Chumash people started speaking a "Proto-Chumash" language that would eventually be spoken throughout the Santa Barbara area. Proto-Chumash is a language that has been reconstructed through the comparative method, which finds regular similaries between languages that cannot be explained by coincidence or word-borrowing, and extrapolates ancient forms from these similarities. Over time, the Proto-Chumash language evolved into Northern Chumash and Southern Chumash languages, from which several languages would evolve and differentiate over time [This is discussed in greater detail below.][1]

During the last 3,500 years or so, the Chumash Indians of Southern California developed many of the cultural characteristics that have led anthropologists to “classify them as one of the most complex hunter gatherer societies in history.” The concept of a Canaliño culture was developed by David Banks Rogers (1929) to refer to the relatively elaborate maritime peoples who occupied the Santa Barbara Channel region at the time of European contact and the millennia just prior to contact. The term was widely used by local archaeologists until the 1960s when the term Chumash was used more often.[2]

The Origin of the Word “Chumash”

The name “Chumash” does not represent a traditional name employed by the aboriginal speakers of related Chumashan languages. According to Sally McLendon and John R. Johnson’s Cultural Affiliation and Lineal Descent of Chumash Peoples in the Channel Islands and the Santa Monica Mountains, “there was, in fact, no single term of self-designation that was used by all the peoples now referred to as Chumash” In fact, the authors noted that the native people in this area were not “a single, homogeneous political, cultural, and linguistic unit.” Furthermore, “the term Chumash… was never used by these people to refer to themselves as a whole; in fact, they did not have a single native word to refer to all the native societies occupying this geographic area.” However, “the word Chumash was originally used by some mainlanders to refer to the residents of Santa Rosa Island (or perhaps of all the inhabited northern islands).”[3]

As a matter of fact, the term Chumash was not used until 1891 and was then employed only to describe the family of languages discussed in John Wesley Powell’s Indian Linguistic Families of America North of Mexico.[4] The term “Chumash” was used to refer to native peoples as a group began with the 1925 publication of the Handbook of California Indians by U.C. Berkeley Anthropologist Alfred Kroeber.

The Present-Day Use of the Word Chumash

Today, Chumash is accepted by many Native American people and researchers as an ethnic designation.[5] As stated in Sally McLendon and John R. Johnson’s Cultural Affiliation and Lineal Descent of Chumash Peoples in the Channel Islands and the Santa Monica Mountains, “linguists and anthropologists today use the name Chumash to designate the native peoples of the North Channel Islands and the central California coast from about Paso Robles in the north to the Santa Monica Mountains in the south.”[6]

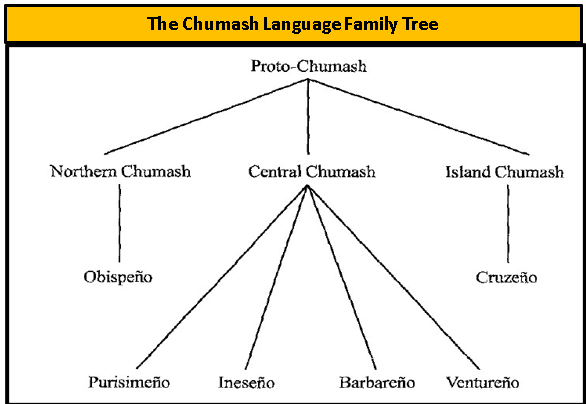

The Chumash Languages Diverge From Proto-Chumash

Although the time of their exact arrival in the Santa Barbara area is unknown, it is clear that their long-time occupation of the area would have created a great deal of diversification in the language of the so-called Proto-Chumash. Through time, all cultures and languages evolve. At some point, this homogenous parent cultural group came under environmental and social pressures which lead to the cultural divergence of the component parts.

When languages diversify, they diverge from a parent language (in this case, Proto-Chumash). Language divergence refers to the process by which a single language splits and becomes two or more distinct languages over time. This can happen due to geographical barriers, cultural isolation, or other factors that lead to differences in pronunciation, vocabulary, and grammar of the parent language.

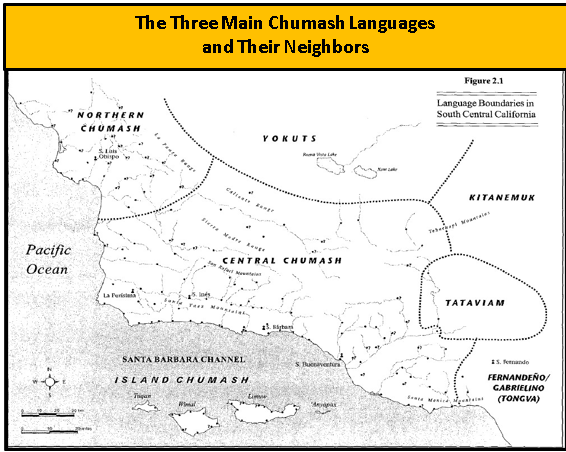

As some members of the proto-Chumash group began to move away from the core group, their cultural and linguistic identity changed and underwent a transformation into a new cultural group. The dialects spoken by similar peoples – when isolated from one another for a period of time – went through a cultural diffusion until, eventually, the resulting groups reached a point where they spoke mutually unintelligible languages. Most studies have grouped the Chumash languages into the following three main divisions, featuring six Chumash primary languages.[7]

1. Northern Chumash (Obispeño)

2. Central Chumash (Purisimeño, Inseño, Barbareño and Ventureño)

3. Island Chumash (Cruzeño)

A map showing the three main Chumash languages and their neighbors has been reproduced as follows:[8]

Map Source: Kathryn Klar, Kenneth Whistler, and Sally McLendon, “Chapter 2: The Chumash Languages: An Overview,” In Sally McLendon and John R. Johnson, Cultural Affiliation and Lineal Descent of Chumash Peoples in the Channel Islands and the Santa Monica Mountains, Volume 1 (Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History, 1999), p. 23.

The Eight Languages of the Chumash People

In his 1925 publication of Handbook of the Indians of California, A. L. Kroeber divided the Chumash territory into eight linguistic divisions, each speaking mutually unintelligible languages that collectively formed the Chumashian language family, which some linguists considered to be a language isolate.[9]

According to Kroeber these eight divisions were geographically contiguous but also exhibited distinct cultural and linguistic features. The Chumash people occupied a wide area from San Luis Obispo to Malibu, extending inland to the San Joaquin Valley. The first five sub-groups were named due to their affiliation with missions that were built within their territories. These territories are illustrated in the following map:

Map by Jonathan Rodriguez.

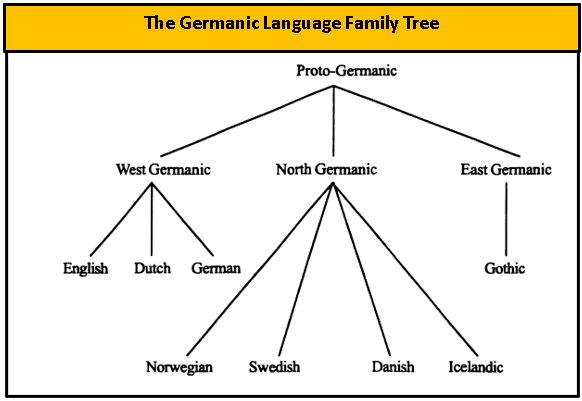

Comparing the Germanic Family to the Chumash Family

As a comparison to the Chumash diversification, Klar, Whistler and McLendon illustrated the divergence of the Germanic language family. The Germanic family of languages consists of three branches: East, West and North Germanic. Each branch was also subdivided into several individual languages. For example, West Germanic includes English, Dutch and German. Meanwhile, the North Germanic consists of the closely related Scandinavian languages: Norwegian, Swedish, Danish, and Icelandic. Each Germanic language shares certain vocabulary and grammatical features with the other languages in the family. Each also has distinct vocabulary and grammatical features and cannot be understood by speakers of other Germanic languages without considerable effort and study. They used a “family tree” diagram to illustrate this:[10]

Map Source: Kathryn Klar, Kenneth Whistler, and Sally McLendon, “Chapter 2: The Chumash Languages: An Overview,” p. 22.

In contrast, the Chumash language family tree diagram follows:

Map Source: Kathryn Klar, Kenneth Whistler, and Sally McLendon, “Chapter 2: The Chumash Languages: An Overview,” p. 22.

The Northern Chumash

The Northern Chumash Language was very different in both vocabulary and grammatical structure from any other language of the Santa Barbara Channel, including even the Central Chumash language Purisimeño, whose territory it bordered.[11] This language was spoken by the Indigenous people living in the area of the San Luis Obispo Mission.

The Island Chumash (Cruzeño)

The Island Chumash (or Cruzeño) also represented “a distinct branch of the Chumash family” and was not easily understood by any of the people who spoke the Mainland Chumash languages.[12]

The Central Chumash

The Central Chumash was considered to be “more complex and diversified” than either the Northern or Island Chumash. The Central Chumash consisted of four main subdivisions: the Purisimeño, Ineseño, Barbareño, Ventureño Languages, all of which were named after the missions where the speakers were baptized and/or married. By the Eighteenth Century, Klar, Whistler and McLendon noted that “speakers of any two geographically contiguous central languages could probably understand each other’s speech” [similar to the mutual comprehension of the people who speak “American English” and “British English”], but any two non-contiguous idioms were probably not mutually intelligible.” For example, the speakers of Purisimeño and Ventureño spoke very different languages (like English and German).[13]

There were several dialects spoken among these languages. However, today, none of the Chumash languages are still spoken today as a medium of communication. But a Chumash cultural revival among Chumash descendants in Santa Barbara and Ventura Counties has given some words, phrases, and songs ritual significance.[14] Today, the language is known as Samala. According to the Santa Maria Times [June 19, 2009, Page B2] the first Samala-English Dictionary was published in April 2008. The 600-page publication featured 4,000 words and 2,000 photographs and illustrations.

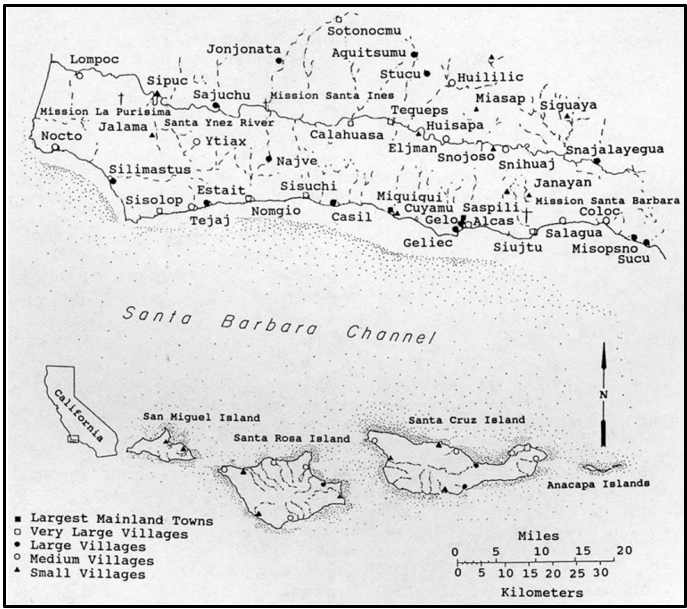

Inhabitants of the Coastal Region

The Chumash Indians had 41 villages along the coastline between the San Buenaventura and Point Concepción. Fifteen more villages were on the Channel Islands off the coast. These coastal native groups sustained themselves by hunting, fishing and seed-gathering. They were described by the Spaniards as gentle, hospitable to strangers, lively, industrious, skillful and clever. Because of their friendly and helpful nature, the Chumash became active participants in the construction of the Santa Barbara Presidio (1782) and the Santa Barbara Mission (1786). The following map shows the Chumash villages in the coastal region.

Map Source: “Historic Chumash Villages” Compiled by Chester D. King from the Notes of John P. Harrington and Other Sources,

in Chester King, “The Names and Locations of Historic Chumash Villages,” the Journal of California Anthropology (Dec. 1, 1975).

Over a span of 65 years, from 1769 to 1834, virtually all of the central and southern California native coastal populations became incorporated into the twenty-one dispersed Spanish mission communities along the California coast. This major event has been attributed to a wide variety of economic, social, and political factors.[15] Over 85 percent of the Chumash migrated to the missions between 1786 and 1803. The abandonment of Chumash villages during this period was not gradual, but rapid.[16]

The Rivera Expedition (1781)

From June to August 1781, the Rivera Expedition journeyed 950 miles from Alamos, Sonora to the San Gabriel Mission. Soon thereafter, the Pueblo of Los Angeles was established (Sept. 4, 1781) with 44 settlers. Most of the soldados de cuera from the Expedition of 1781 stayed at San Gabriel to prepare for their next assignment, which would be the establishment of San Buenaventura (now Ventura) and Santa Barbara.

The Journey to Santa Barbara (1782)

Santa Barbara lies along the Pacific Ocean almost 100 miles northwest of Los Angeles. In those days, the Santa Monica Mountains, Tehachapi Mountains, and the San Gabriel-San Bernardino Mountain range represented a formidable barrier to north-south travel for Spaniard and Indian alike. Southeast of present-day Santa Barbara, the Santa Monica Mountains drop off abruptly into the Pacific Ocean. Armed expeditions seeking to travel through the area northward to Monterey had to thread their way carefully along the coastal Indian trails in the beach area. During the winter rainy season, the route was almost impassable for horses and mules.

According to Monsignor Francis J. Weber in his work, Queen of the Missions, the purpose for establishing the Santa Barbara Presidio was to “hold California together.” He stated that Felipe de Neve “saw that the Santa Barbara Channel was a danger spot because the mountains came right down to the sea. Any road cutting through the area would have to run closer to the shoreline. And if the large Indian population should rise to revolt, the narrow passage might easily be blocked and California would be cut in half.” As a result, de Neve planned to establish three missions and one presidio along the Santa Barbara Channel in a very short period of time (1782-1787)

The Expedition Moves North to Santa Barbara (1782)

Heavy rains during the Autumn and Winter of 1781/1782 delayed the Santa Barbara expedition until the spring of 1782. As a result, the soldiers and their families stayed in their forty small palisade huts at the San Gabriel Mission. On March 26, 1782, the Santa Barbara Company consisting of fifty-seven officers and men under the command of Lieutenant Ortega finally left San Gabriel. The entire expedition numbered some 200 people, including muleteers with trains of utensils and food supplies, Indian auxiliaries, wives and children, as well as 200 horses and mules.

On March 29, 1782, the Santa Barbara Company reached San Buenaventura where the ninth Alta California mission was founded by Father Serra. The entire expedition became involved in the construction of the chapel and dwelling places during the next two weeks. On April 24, 1782, Governor de Neve was able to report to his superior officer that the Mission of San Buenaventura had been completed, indicating that the natives of the region were pleased with the presence of the settlement.

On April 15, 1782, Governor de Neve assembled forty-two soldiers to resume the expedition toward Santa Barbara. Sergeant Pablo Antonio Cota and fourteen soldiers were left in San Buenaventura to protect the mission and to continue with the building. The expedition marched twenty-seven miles along the coast between the Pacific Ocean and the high cliffs flanking the shoreline. For much of the first ten miles, the soldiers had to walk through the surf at the base of the cliffs. They found several Indian villages along the way.

The Establishment of the Santa Barbara Presidio (1782)

On April 21, 1782, Governor de Neve and Lieutenant Ortega found a good site for the new presidio near an Indian village. The site was elevated above the surrounding area and could thus provide a view of incoming ships and possible attack by hostile Indians. The site also had good drainage and was close enough to shore for transporting supplies that would deliver supplies. At the same time, the presidio was far enough from the shore to be out of cannon-reach of any enemy ships (possibly the English fleet). Feeling uneasy about the large Indian population in the area, Governor de Neve felt that the fortifications should be built, and the security of the presidio guaranteed before any construction began on the Mission.

The Establishment of the Santa Barbara Mission (1787)

Feeling uneasy about the large Indian population in the area, Governor de Neve felt that the fortifications should be built, and the security of the presidio guaranteed before any construction began on the Mission. Therefore, the building of the Santa Barbara Mission did not begin until 1787. Santa Barbara was the first mission founded by Padre Serra's successor, Padre Fermin Francisco de Lasuén. La Purisima Concepción Mission was the eleventh mission built a year later (on December 8, 1787) at present-day Lompoc, over 50 miles northwest.

The Missions in the Chumash Region

There were more missions established among the Chumash than among any other Native American group in California. Five missions were founded in Chumash territory: San Luis Obispo (1772), San Buenaventura (1782), Santa Bárbara (1786), La Purísima Concepción (1787) and Santa Ynez (1804). But some Chumash also attended church services at the Mission San Fernando (founded in 1797), which was in the territory of the neighboring tribe to the east, the Tataviam.

The Political Structure of the Chumash

Politically, the Chumash were divided into a number of independent polities composed of relatively large villages, or groups of villages, organized around the limited authority of a hereditary chief (Arnold 1992; Johnson 1988). The most important chiefs, who lived in the largest coastal villages and owned the community's canoes, derived much of their wealth and power from their ability to control and manage exchanges among the island, coastal, and inland villages. Intervillage hostilities were a frequent occurrence and involved conflicts between groups of federated villages.[17]

The Natives Living in the Santa Ynez Region

Chumash villages in the Santa Ynez area ranged in size from a low of fifty persons to a high of more than five hundred individuals. The population level for the entire Chumash region has been estimated to be in excess of fifteen thousand people.[18]

Choosing the Site of the Mission

After completing the initial coastal chain of missions to the north, Father Lasuén directed Father Estevan Tápis of Mission Santa Barbara to accompany Captain Felipe de Goycoechea to survey possible mission sites northeast of the coastal mountains. In the fall of 1798, an expedition under Captain Felipe de Goycoechea surveyed the Calahuasa Ranchería (where the Santa Ynez Indian Reservation is now) and another Chumash site called Alajulapu (presently Solvang). Father Fermin de Tápis reported that there were 1,200 native people living in 325 dwellings at 14 rancherías in and near Calahuasa.[19]

The site deemed to be the best site for the mission was Alajulapu which was about two-and-a-half leagues northwest of Calahuasa. It was also known by some as Majalapu. The "Reconocimiento de Calahuasa" dated Oct. 23, 1798, is Document 404 (old 331) located at the Santa Barbara Mission Archives today. At the end of the report is an important list of villages in the Santa Ines region.[20]

The New Mission Site Is Approved

Father Lasuén reported the findings to Governor Diego Borica. In turn, the Spanish Viceroy Iturrigaray approved Calahuasa as a suitable site for a new mission.[21] However, it would be six years before the Franciscans could establish their new Mission. The governor died, so approval was then needed from his successor, Jose de Arrillaga, in Baja California.

In February 1803, it was ordered that the mission should be established. On March 2, 1803, José Joaquín de Arrillaga ̶ who had succeeded Borica as Governor of California ̶ approved the locality called Calahuasa.[22] Dr. John R. Johnson counted a total of 15 Ineseño villages within the Santa Ynez watershed. He indicated that there were a total of 22 Chumash villages located within the entire Santa Ynez Valley, but seven of them were likely occupied by Purisimeño speakers (belonging to La Purísima Concepción Mission).[23]

The Mission is Established (September 1804)

On September 17, 1804, Mission Santa Inés was established as the 19th of the 21 California Missions established by the Franciscan Fathers. The mission was named for Santa Inéz [Saint Agnes in English] who was martyred in Rome in the Fourth Century at the age of 13. The mission site was located just north of the Santa Ynez River near three of the Ineseño villages: Alaxulapu, Calahuasa [Kalawashaq], and Anaxuwi. The spot was well-watered and contained pastureland for livestock and good soils for growing crops like wheat and barley.

Baptisms on Santa Ynez’s First Day

On Sept. 17, 1804, the founding of Santa Ynez was a festive affair. Father Estevan Tápis, the Padre Presidente of the Alta California Missions, in his report of June 30, 1803, to Governor Arrillaga, described the occasion, stating that many people came from San Luis Obispo and Santa Barbara, including over 200 gentiles [Indigenous people who were not yet Christianized]. Comandante Jose Raymundo Carrillo of the Santa Barbara Presidio attended and acted as a padrino [godfather] to twelve male infants that were baptized that afternoon.[24]

The eighth baptism was performed on a 3-year-old native boy named Ayehuiya from Sotonocmu. With this baptism, Ayehuiya became a Christian named Gregorio. He was listed as a son of gentiles, including his father Samuyaucta, who would later be baptized as Vitaliano. Gregorio’s godfather was the soldier Jose Raymundo Carrillo. Father Tapis baptized 27 children of natives on the day he founded Santa Ynez. On the same day, fifteen male adults were dressed for catechetical instruction. They included the three chiefs of the rancherias Calahuasa, Soctonocmu, and Ahuama.[25]

Vitaliano: The Father of Two Generations of Chiefs

Later in the year, on December 28, 1804, the gentile man named Samuyauta, the 22-year-old father of Gregorio, a native of Sotonocmu like his son, was baptized. Samuyauta was baptized under the Spanish Christian name of Vitaliano [Santa Ynez Baptism #89]. Four days earlier, on Dec. 24, 1804, a younger sister of Gregorio was also baptized at Santa Ynez. At the time, she was three years old and said to be from the Ahuam Rancheria. Her father was Vitaliano (aka Samuyauta) and her mother was Nicolasa. Both her parents were described as “catecumenos” (persons receiving instruction in the Christian faith, or converts). Vitaliano’s baptism is shown below:

The Baptism of Nicolasa

Three days later, on Dec. 31, 1804, Vataliano’s wife, Nicolasa, would also be baptized at the mission [Santa Ynez Baptism #103]. She was the one hundred and third person to be baptized at the mission and was said to be from the Sotonocmo Rancheria. Nicolasa was 20 years old and mentioned as the mother of Ygnacia and the wife of Vitaliano (who had been baptized as No. 89).

The Marriage of Vitaliano and Nicolasa

On the same day shortly after Nicolasa’s baptism, Vitaliano and Nicolasa were married in a Catholic ceremony at Santa Ynez [Santa Ynez Marriage #15 (12/31/1804)]. As noted in the document below, Vitaliano’s native name Samuyauta was given and he was described as the father of Gregorio [Baptized as No. 6] and Ygnacia [Baptized as No. 80]. Meanwhile, Nicolasa had no native name and was just called the mother of Ygnacia. Their respective Baptism numbers were given as No. 89 and No. 103. They would become the parents and grandparents of several Santa Ynez chiefs during the Twentieth Century.

At The End of the First Year

At the close of 1804, after four months of operation, Santa Ynez Mission had baptized 112 Indian converts of all ages from the surrounding area.[26] A padrón (or tally) of the mission parishioners at the end of 1804 reported that 116 male Indians and 109 female Indians living at Santa Ynez. Although this amounts to 225 neophytes, roughly half of them had come from adjacent missions and had already been baptized. However, in 1806, a measles epidemic swept through the mission, killing many neophytes. In later years, more epidemics would sweep through the mission.

Chumash Towns In the Area of the Three Missions

The Figure 3.1 Map entitled “Chumash Towns at the Time of European Settlement” in Kathryn Klar, Kenneth Whistler, and Sally McLendon work show the Chumash towns [known as rancherias] in the immediate vicinity of the three main missions, La Purisima Concepción, Santa Ynez, and Santa Barbara: [27]

The Leaders of the Chumash

John R. Johnson, in his Ph.D. dissertation, Chumash Social Organization: An Ethnohistoric Perspective (University of Santa Barbara, 1988), had noted that the baptisms of high-ranking chiefs of some of the rancherías played a role in the conversion and baptism of other Chumash individuals.[28]

As an example, an important regional chief, Yanonali, presented himself for baptism at Mission Santa Barbara on September 12, 1797, and was given the Spanish name Pedro. Yanonali resided at the large Indian village at Syuxtun near the beach in present-day Santa Barbara and claimed authority over this and twelve other villages. At the time, he had at least three wives. Although he had been acquainted with the Spanish since at least 1782 when they founded the presidio at Santa Barbara, he did not get baptized for 15 years. According to Dr. Johnson, “Yanonali’s friendship was actively sought.” Other members of his village were given the unique “privilege” of remaining in their village after they accepted conversion rather than having to move to the mission.[29]

Dr. Johnson provided two tables showing the marriage and residence information for the chiefs from the coastal villages (Table 6.6) and from the Inland villages (Table 6.7) that provide a good picture of the leadership of these villages at the time of the Spanish settlement.[30] These tables have not been reproduced here.

The Santa Ynez Mission (1806-1824)

By the beginning of 1806, the Santa Ynez Mission rolls carried a total of 570 neophytes, including many of whom were already baptized at the nearby missions of Santa Barbara and La Purísima Concepción.[31] By 1810, there were 628 neophytes at Santa Ynez, with 546 baptisms having been recorded.

From 1804 to 1812, an extensive building program was carried out, and in the year 1812, more than 80 houses were built. In 1812, the population of Chumash at the Mission reached 718, the highest number of the entire Mission Era. These Chumash included those from Mission Santa Barbara and La Purisima Concepción, who had come to the new Mission to help train the local population. However, the Dec. 21, 1812 earthquake “rendered the church unserviceable and demolished the walls of many of the mission buildings.” A new church had to be erected to serve as a church in 1813, and a new church was dedicated in 1817.[32]

After the beginning of the Mexican War of Independence against Spain in 1810, financial support to the missions ceased. The missions were required to become self-sustaining. Because the soldiers were no longer receiving their salaries and the annual ship from San Blas carrying provisions for the soldiers and their families was also cancelled, the officers at the Presidio made greater demands on the Missions to supply food and clothing to the soldiers and their families.

From December 1808 to 1824, Father Zephyrin Engelhardt noted that Father Francisco Xavier Uria had been in charge of Santa Ynez and “had transformed the Mission into an active and thriving community of neophytes. The converts had steadily increased, as the baptismal register demonstrates.” Up to December 8, 1808, there had been 441 baptisms performed at the mission. By February 17, 1824, when Father Uria performed his last baptism, he had baptized 1,227 people in all.[33]

At the end of 1823, the neophyte Indian community at Santa Ynez consisted of 217 male adults, 84 male children, 210 female adults and 53 girls. That amounted to 301 male Indians and 263 female Indians for a total of 564 neophytes.[34]

The Santa Ynez Revolt (1824)

On February 21, 1824, the Indians at Santa Ynez rebelled, and the uprising soon extended to the nearby missions. The revolt began when a visiting Chumash Indian from La Purísima and a Corporal Cota got into an argument which turned into a fight and then a flogging. According to Father Zephyrin Engelhardt, O.F.M., the Archbishop’s Archives, No. 1739 indicate that “the revolt was not against the missionaries; on the contrary, the revolting Indians wanted to have the Fathers go along with them. The revolt came about because they were made to work in order to maintain the troops, and nothing was given them in payment, as they said.” But “to the increasing disgust of the Indians,” the neophytes at the mission were taxed heavily.[35]

Most of the Santa Inés mission complex was burned down. However, when Mexican military reinforcements arrived, the native insurgents withdrew from Mission Santa Inés and then attacked Mission La Purísima Concepción. They forced the small garrison to surrender, and allowed the garrison, their families, and the mission priest to depart for Santa Inés in peace. The next day, the Chumash of Mission Santa Barbara captured the mission from within without bloodshed, repelled a military attack on the mission, and then retreated from the mission to the hills.

By March, most of the insurgency had ended when a Mexican military unit had been called into the area. In June, a Mexican military expedition negotiated with the Chumash and convinced a majority of them to return to the missions by June 28. In total, the rebellion involved as many as three hundred Mexican soldiers, six Franciscan missionaries, and two thousand Chumash and Yokuts people of all ages and genders.

Drawing by Edward Vischer depicting the Mission Santa Ynez as seen from the north, 1865.

Secularization (1834)

From the beginning of Mexican rule, the specter of secularization had haunted the mission system. Finally, on August 2, 1834, the Legislative Assembly passed a decree secularizing all the missions of California, and Govenor Jose Figueroa announced the new law.[36] In essence, this meant converting the missions into parish churches. The Spanish Franciscans in California were replaced by Mexican Franciscans who were allowed to provide only for the spiritual needs of the Chumash (but were not allowed to convert natives).

Half of the mission property would go to the Indians and the other half would be used for agriculture and other needs. The neophytes would also be freed of mission control and the mission lands would be open to them. In time, the Franciscan priests at Mission Santa Inés were replaced with government-appointed administrators, or comisionados, who oversaw the transition. This process ultimately led to the mission's lands being divided and sold to Mexican ranchers, rather than being returned to the native people as originally promised.

Many of the neophytes did not have an understanding of land ownership. As it had been in the pre-Hispanic times, they thought the land shoud be available to everyone. Under the new policy, the Chumash were treated badly and many of them returned to their villages or went to work on local ranches. Some Indigenous people stayed close to the mission because their villages [rancherías] no longer existed.

The Family of Vitaliano and Nicolasa

By the early 1820s, the Indigenous couple, Vitaliano and Nicolasa, were raising their family within the Santa Ynez Indian community. According to Santa Ynez Mission records, they had the following children over the course of the next two decades:

1. Ygnacia, baptized Dec. 24, 1804 (Baptism #80) (3 years old)

2. Gregorio, native name Ayehuiya, baptized Sept. 17, 1804 (Baptism #6) (3 years old)

3. Miguel, baptized Sept. 29, 1807 (Baptism #405)

4. Francisca Xavier, baptized Dec. 24, 1808 (Baptism #443) (3 years old)

5. Maria de la Trinidad, baptized June 9, 1811 (Baptism #566)

6. Angel, baptized March 30, 1813 (Baptism #642) (1 year old)

7. Cyriana, baptized Sept. 27, 1815 (Baptism #788) (1 year old)

8. Ynes, baptized Jan. 28, 1818 (Baptism #1039)

9. Rafael, baptized April 16, 1822 (Baptism #1180) (born after the death of his father)

At least two of these sons – Angel and Rafael – would become recognized chiefs of the Santa Ynez Mission Indians during the American period. However, Vitaliano died on Oct. 27, 1821 (Santa Ynez Burial #847) and was buried in the cemetery of Santa Ynez Mission. The burial record stated that his spouse was Nicolasa. Her burial took place four years later on August 27th, 1825.

The Baptism of Rafael (1822)

Rafael, the future chief of the Santa Ynez tribe, was baptized on April 16, 1822, almost seven months after his father’s death [Santa Ynez Baptism #1180]. His baptism has been translated as follows and has also been reproduced below:

Translation: On the 16th of April of 1822, in the church of this mission of Santa Ynez, I baptized solemnly a legitimate son of the deceased Vitaliano and of Nicolasa, baptized and gave him the name of Rafael. The godparents were Manuel, married with Maria del Amposa, whom I advised of the spiritual parentage and other obligations, and in witness thereof I signed…

The Marriage of Angel and Tomasa (1837)

Another son of Vitaliano was Angel, the sixth-born child of Vitaliano and Nicolasa. On October 10, 1837, 24-year-old Angel was married to Tomasa at the Santa Ynez Mission [Santa Ynez Marriage #427]. That marriage has been reproduced below and is translated as follows:

In the Margin: 427. Angel, single, with Tomasa.

Partial Translation: In the year 1837, on the 10th of the month of October, after reading the three admonitions in three continuous holidays [Sundays] on the 10th of Sptember, the 17th and the 24th, and no legitimate impediment [to marriage] resulting, I, Father Joaquin Simona, Minister of the Mission of Santa Ynes, married Angel, single, son of the deceased Vitaliano and Nicholasa, to Tomasa, widow of Pedro Regalado, neophytes of this mission…

Angel and Tomasa had six children, all baptized at Santa Ynez Mission, as noted below:

1. Crescente, Baptized 06/27/1838 (#1442)

2. Domitila, Baptized 06/11/1840 (#1466)

3. Baldomero, Baptized 03/02/1842 (#1494)

4. Juan, Baptized 07/12/1845 (#1553)

5. Jose Dolores, Baptized 01/11/1848 (#1586)

6. Estevan, Baptized 12/26/1849 (#1622)

Two of their children became known as chiefs of the Santa Ynez band: Dolores and Estevan. On January 11, 1848, Santa Ynez Baptism #1586 reveals that Angel and Tomasa baptized their fifth-born child, Jose Dolores. A partial translation indicates:

Partial Translation: In 1848, on the 11th of the month of January, Father Francisco Sanchez baptized a son of Angel and Tomasa, a married couple of this Mission of Santa Ynez, whom I gave the name of Jose Dolores…

The Mexican American War (1846-1848)

In 1845, the United States annexed the independent Republic of Texas [which had declared its independence from Mexico in 1836]. Seeking to provoke Mexico even more, President James K. Polk sent a military expedition to the Rio Grande Valley to assert American claims to the Nueces Strip in January 1846. After Mexican and U.S. troops clashed near the Rio Grande River in April 1846, on May 13, 1846, the U.S. Congress declared war on Mexico.

On July 7, 1846, the United States flag was raised at Monterey and all of California became part of the United States. In August, 1846, Commodore Robert Stockton occupied Santa Barbara and left a garrison of eleven soldiers. Two months later, they were driven out by local Californios. In December 1846, Colonel John Fremont retook the community with a force of 450 men. He arrived via San Marcos Pass, avoiding an alleged ambush set for Gaviota Pass, and found no resistance.

However, the war raged on for almost two years, ending on February 2, 1848 with the signing of the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. This treaty transferred 525,000 square miles of land from Mexico to the United States. The land ceded included present-day California, Nevada, Utah, New Mexico, most of Arizona and Colorado, and parts of Oklahoma, Kansas, and Wyoming. In addition, the U.S. paid $15 million to Mexico. The following map shows the large amount of territory that changed hands at that time:

Source: “We Didn’t Cross the Border. The Border Crossed Us!” (May 6, 2010). Online: https://coffeeforclosers.wordpress.com/2010/05/06/we-didnt-cross-the-border-the-border-crossed-us/.

California Statehood (1850)

California became the thirty-first state of the United States on Sept. 9, 1850. At that time, much of its geography was still a mystery, and the count of its Indian population continued to be conjectural, with estimates varying from 50,000 to 300,000. With the American takeover, the United States government agreed in the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo to honor land rights as they existed under the previous (Mexican) regime. On March 3, 1851, Congress approved the Land Claims Act, which set forth a process for proving claims.

The Indigenous Decline Continues

It has been estimated that there were between one and two hundred thousand Indians in California when Commodore John Drake Sloat raised the Stars and Stripes at Monterey in 1846. From 1849 to 1856 alone, the decrease in the Indian population probably numbered 50,000. Disease and liquor conspired with bullets and knives to wreak havoc upon the Indian population.[37]

The Mariposa War (1850-1851)

The Mariposa War (December 1850 – June 1851), also known as the Yosemite Indian War, was a conflict between the United States and the indigenous people of California's Sierra Nevada in the 1850s. The war was fought primarily in Mariposa County and surrounding areas and was sparked by the discovery of gold in the region. The Mariposa War was very provocative in making many European American settlers ponder “the Indian Problem.” As a result, in the years to come, the United States government, California state government, and White settlers enforced deliberate policies of displacement, forced removals, and massacres that drove Native Americans from their traditional lands and onto reservations.

The Appointment of Three Commissioners

California's two U.S. senators, John C. Fremont and William M. Gwin — a slaveowner from Mississippi who controlled California's political machine throughout the 1850s — proposed to extinguish any and all Indian land claims. Over time, this is what happened. The U.S. Senate authorized, and President Millard Fillmore appointed three commissioners to negotiate treaties with the California Indian tribes — George W. Barbour, Redick McKee and O.M. Wozencraft.[38] What they did was, in the words of Stanford University anthropologist Robert F. Heizer (1972), "a farce from beginning to end." The three commissioners arbitrarily divided California into 18 regions. Each of the 18 regions contained numerous ethnic groups, and each of California's ethnic groups consisted of several small, autonomous tribal groups with their own clan leaders. No one person spoke for all the Indigenous people of California.

Between March 19, 1851, and January 7, 1852, Commissioners McKee, Barbour, and Wozencraft had negotiated a total of eighteen treaties with the California Indians. Eventually 139 of the state’s 300-plus tribal groups signed 18 treaties that gave away their sovereign rights in exchange for 7.4 million acres of “reservation” lands (1/14th of the state) spread across the state.[39]

On June 10, 1851, a treaty was signed at Tejon Creek by the leaders of eleven tribes from the southern San Joaquin Valley region. This included several people who spoke Chumash languages who had formerly resided at Missions San Fernando, San Buenaventura, and Santa Barbara. These tribes ceded any claim to Area 286 to the Anglo-Americans. The tribes agreed to inhabit Area 285, a reservation comprising 763,000 acres. The Tejon Reservation was subsequently established in September, Î853, in Area 311 [as noted in the following map].[40]

The Eighteen Treaties Are Rejected (1852)

The eighteen treaties were submitted to the United States Senate, June 1, and on June 8, 1852, they were individually and collectively rejected in a secret session of that body. Public sentiment at this time was firmly against cooperation with the Native American population. [41] The Senate wished the 18 treaties away, hiding them under lock and key until they were unsealed in 1905, by which time the plight of Indians in California and the Southwest was beginning to register on the public conscience.

The Sebastian Indian Reservation

The Sebastian Indian Reservation (1853–1864), more commonly known as the Tejon Indian Reservation, was at the southwestern corner of the San Joaquin Valley in the Tehachapi Mountains of Southern Central California. The reservation became operational in September 1853, and some California Indians moved in voluntarily. Among the tribes of Mission Indians the reservation held, were 300 Emigdiano Chumash, whose homeland had included Tejon Canyon. In 1854, Lieutenant Beale reported that 2,500 Indians were living on the Sebastian Reservation. However, both droughts and floods took their toll on the reservation between 1861 and 1863. Also in 1863, the agent Edward F. Beale purchased five contiguous ranchos in the Tejon area, which took in parts of the reservation land. Finally, the reservation was ordered to close and was abandoned in 1864.[42]

Chief Rafael and the Indians in the 1852 Census

In the California Special Census of 1852, the Indigenous inhabitants of Santa Barbara were listed on page 14. Working as a vaquero (cowboy), 32-year-old Rafael [the son of the deceased Vitaliano], who was reognized by many as the Chief of the Santa Ynez tribal group was at the head of the household. Listed below Rafael was his 28-year-old wife, Catalina, who had been baptized at Santa Ynez on October 25, 1834 [Santa Ynez Baptism #1357] who had married Rafael on Dec. 21, 1842 [Santa Ynez Marriage #453]. Listed below Catalina was their 12-year-old son, Manuel del Refugio, who had been baptized at Santa Ynez Mission on Dec. 28, 1842 [Santa Ynez Baptism #1541].

Listed farther down on the same page as Chief Rafael in the same group of Indians was the 40-year-old vaquero Angel. Angel, another son of Vitaliano and Nicolasa, had been baptized on March 30, 1813 [Santa Ynez Baptism #642] and was a younger brother of Chief Rafael. Listed next to him was his 30-year-old wife, Tomasa, whom he had married on Oct. 10, 1837 [Santa Ynez Marriage #427].

And they had their children listed as well, including two well-known figures in late 1800s and early 1900s. Jose Dolores, the son of Angel and Tomasa, had been baptized at the Santa Ynez Mission on Jan. 11, 1848 [Santa Ynez Baptism #1586]. His obituary printed 25 years after his death in the Santa Maria Times on Feb. 25, 1938 reported that he died from injuries from a holdup attack. His younger brother, 2-year-old Esteban, was baptized at Santa Ynez on Dec. 26, 1849 [Santa Ynez Baptism #1622]. Esteban would also become well known, receiving a nice obituary in the Santa Maria Times on Jan. 31, 1930. Both men became known by the surname Solares later in the American period.

Rancho Cañada de los Pinos

In 1853, Archbishop Joseph Sadoc Alemany (the Catholic Archbishop of San Francisco from 1853 to 1884) filed petitions for the return of all former mission lands in the state. As required by the Land Act of 1851, a claim for Rancho Cañada de los Pinos (later known as the College Rancho) was filed with the Public Land Commission in 1853, and the grant was patented to Bishop J. S. Alemany in 1861. The College Rancho consisted of 36,000 acres of land close to the Mission. This rancho encompassed Mission Santa Ynez and the present-day City of Santa Ynez.[43] The College Rancho was given to the Seminary of Santa Ynez and remained in the hands of the Catholic Church after the secularization. According to the Directory of 1854, the Diocesan Seminary and the College of our Lady of Guadalupe at Santa Ynez had 12 students and two professors. Later in the decade, the number of students would increase, reaching 25 students by 1859.[44] Around this time, in August 1846, Father Juan Comapla’s inventory showed that there were 109 surviving Santa Ynez Indians. These included 55 males and 54 females.[45]

Chief Rafael in the 1860 Census

It is noteworthy that in the 1860 census, the Santa Ynez community took up less than 20 pages in the census schedules. Rafael, the chief, was in household 31, with his son Manuel and an 18-year-old woman named Refugia. Forty-year-old Rafael was listed as a male Indian who owned $50 of real estate and $100 of personal state. Maria may have been his new wife, as Catarina had died three years earlier. Listed also was Rafael’s 18-year-old son, Manuel. Below Manual was his 12-year-old sister, Maria Paula, who had been baptized at Santa Ynez on June 27, 1847 [Santa Ynez Baptism #1581]. Farther down the list was 18-year-old Refugia. Although Refugia/Refugio was a common first name for many Indian girls at Santa Ynez, it is likely that this is the woman who later became known as Maria Refugio Solares and married Manuel in 1872.

Chief Angel in the 1860 Census

Listed on the next page in the census in Household 32 was Chief Rafael’s brother, 45-year-old Angel, who also became a chief later on. His 45-year-old wife, Tomasa, was also listed. Listed with their parents were 15-year-old Jose Dolores and 11-year-old Estevan, who later became tribal chieftans in their own right.

Manuel Marries Maria Refugio (1872)

On the 21st of April 1872, Manuel, the son of Chief Rafael and Catarina [Catalina], was married to Maria, the widow of Nicomede [Nicomedes] at the Mission Santa Ynez [Santa Ynez Marriage #574]. Maria was described as an Indian and the daughter of the deceased Benvenuto and of Brigida. The witnesses were Manuel’s brother Angel and his wife Tomasa. Later, Maria would be known as Maria Refugio Solares and, today, she is simply known as Maria Solares.

Maria Solares As A Cultural Icon

Maria Solares, the wife of Manuel, today is a cultural icon of the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians. She later collaborated with J.P. Harrington, an American linguist, ethnologist, and a specialist in California tribes. He gathered more than one million pages of phonetic notations on languages spoken by the tribes. Many of the pages from his notes and audio recordings included his discussions with one of his informants, Maria Solares.[46] From 1914 to 1919, Maria gave vivid descriptions to Harrington about the daily life, traditional stories, history, and genealogy of the Samala Chumash before Spanish contact in the 1700s. In a 2007 newspaper commentary, Richard Gomez stated that through “Harrington’s documents and recordings… we have been able to recapture the spirit and tradition of our tribe’s rich cultural heritage as well as our language.”[47]

The Baptism of Maria Ysidora Refugio Solares (1842)

Maria Ysidora del Refugio was baptized in the Chapel of Monterey, a subsidiary of Santa Clara Mission, but her parents, Benvenuto and Brigida were Indian neophytes living in the vicinity of the Santa Ynez Mission. Her baptism has been reproduced and translated below [Santa Clara Baptism #4385].

Translation of Maria Ysidora del Refugio Baptism:

In the Margin: 4571. Maria Ysidora del Refugio. India. 4385.

Text: On April 30, 1842, in the Chapel of Monterey, I baptized solemnly and poured the holy oil and sacred chrism on a girl 15 days after birth, legitimate daughter of Benvenuto and Brigida, neophytes of the Mission of Santa Ynez, whom I gave the name of Maria Ysidora del Refugio, her godparents were Ricardo Juan and Maria Josefa Rodrigues, whom I advised to their duty; and in witness thereof I signed it.

The Maternal Ancestors of Maria Ysidora del Refugio

Although a few people have questioned Maria Solares’ credentials as a bona fide daughter of the Santa Ynez Mission Indians, research into her ancestors has proved that she easily qualifies as a genuine member of the Santa Ynez [or Zanja Cota] Mission Indians. On October 13, 1837, Maria Ysidora del Refugio’s parents, Benvenuto and Brigida, were married at Santa Ynez Mission [Santa Ynez Marriage #428]. Brigida had come from the area of Kern County and was the daughter of gentiles [non-Christians] named Seget and Schajo, whose names were revealed in the January 7, 1832 baptism of Brigida’s brother, Raymundo [Santa Ynez Mission Baptism #1322]. Less than a decade before Maria’s baptism, Brigida herself had also been baptized at Santa Ynez on December 23, 1834 (Santa Ynez Baptism, #1369) as a 16-year-old native girl known as Shiguashapen from the Rancheria of Teneshah. Teneshah was located near present-day Stallion Springs in Kern County, California.

The Paternal Ancestors of Maria Ysidora del Refugio

Although her mother’s family came from what is now Kern County, Maria Solares’ father, Benvenuto, had deep roots in the region, with his family coming from the Ranchería de Calahuasa. Maria Refugio’s paternal grandfather was known by the native name of Colocutayiut before he became a neophyte of the Santa Ynez Mission. He was baptized as Estevan on June 1, 1805 at Santa Ynez [Santa Ynez Baptism #203]. Estevan’s mother Modesta [the great-grandmother of Maria Refugio] was baptized a year later on June 27, 1806 [Santa Ynez Baptism #306].

The Marriage of Estevan and Eulalia

Two months after his baptism on August 2, 1805, Estevan Colucutaguit of Ranchería de Calahuasa was married to Eulalia, who was also from Calahuasa. This marriage record of Maria Solares’ grandparents has been reproduced and translated below:

Translation: On the 2nd of August 1805, having already baptized solemnly in the Church of this Mission of Santa Ynez, I married and veiled Eulalia, native of the Rancheria Calahuasa… contracted in marriage with the gentile Estevan Colucutaguit of the said Ranchera [Calahuasa] and married them in the face of the church; the witnesses of their consent were Luis Marianta and Joseph Maria Juaniaset, their baptisms were numbers 203 and 227.

Eulalia was the 27-year-old daughter of Calisto (“Sicumait) and Dominga, who had also been married on April 26, 1805 [Santa Ynez Marriage #44]. She had been baptized the previous day [Santa Ynez Baptism #227], which has been translated as follows:

Translation: On the First of August of 1805, I baptized solemnly in the Church of this Mission of Santa Ynez an adult female of 27 years of age, a native of the Rancheria Calahuasa, daughter of Calisto Sicumait and Dominga, baptized as numbers 135 and 187, and woman (wife) of Estevan Colocutayiut, baptized as No. 203 and mother of Maria Casta and Francesca, neophytes of Santa Barbara and whom I gave the name Eulalia; her godmother was Maria del Rosario, wife of Joaquin Ahuihuluichet, whom I advised of her obligations, and in witness thereof I signed it.

It is noteworthy that Eulalia was not married in the church to Estevan until the next day, but even in her baptism she was already considered his spouse, which implies that they were already living as husband and wife.

The Marriage of Benvenuto and Brigida (1837)

With Maria Solares’ paternal ancestors getting baptized and married in 1805, during the year after the Mission Santa Ynez was established, it is clear to see that her credentials as a daughter of the Santa Ynez Mission have been established, in spite of the fact that she was baptized in Monterey. The two-page marriage of her parents, Benvenuto and Brigida, is not reproduced here, but the translation of the marriage follows [Santa Ynez Marriage #428]:

Translation of Marriage Document: In the year of 1837, on the 13th of October, I read the three warnings (marriage banns) on three continuous festive days in the main Mission, of which the first was the 24th of September, the second the First of October, the third was on the 8th; and no impediments [to marriage] resulting, I, Jose Joaquin Damian Montez of this mission of Santa Ynes, married Benvenuto, son of Estevan and Eulalia, single man, and Brigida, single woman, daughter of Gentile [non-Christian] Indians, a neophyte of this mission. I asked them in the church for their mutual consent, I married them solemnly by the words of [the people] present… the witnesses present were known as Joaquin Ayala, spouse of Tomasa, and Andres, spouse of Luisa…

The Children of Benvenuto and Brigida

The known children of Benvenuto and Brigida who were baptized at the Santa Ynez Mission were:

Jesus, baptized March 21, 1838, Santa Ynez Mission

Epigmenio, baptized March 21, 1839, Santa Ynez Mission; died about May 2, 1841.

Maria Ysidora del Refugio, baptized April 15, 1842, Monterey, died on March 6, 1923.

Jose Maria, born about April 1847, Santa Ynez, died on May 7, 1847 in Santa Ynez.

Jose de la Cruz, born July 1848, Santa Ynez, died on July 30, 1848 in Santa Ynez.

Jose Tomas, born December 1849, Santa Ynez, died on Dec. 24, 1849 in Santa Ynez.

It is believed that only Jesus (born in 1838) and Maria Ysidora del Refugio (born in 1842), survived their first year of life. Some accounts claim that Maria Ysidora del Refugio may have had as many as nine brothers and sisters and that none of them survived, essentially making her an only child.[48] Maria Refugio Solares would be married at least four times and had at least four known children who lived to be adults: Maria Antonia Ortega (born 1862), Clara Candelaria Liberado (born 1867), Francisco Estrada (born 1870), and Jose Solares.

Brigida and Maria Refugio Solares in the 1870 Census

Although the 1870 census did not record many people classified as “Indians” in the Santa Ynez area [Township 3 of Santa Barbara County], Brigida was listed with her small children in Dwelling #315, Family #317. Her husband Benvenuto had died the year before and her own age was off by many years. In the 1870 census, Brigida (spelled Brigita) was listed as a 40-year-old woman who “keeps house” and owned $325 in personal property and $100 in real estate. She was also listed as “W” for White, an apparent mistake of the census taker.

Living with her was her 26-year-old daughter Maria (later known as Maria Refugio Solares) who was listed as “W” (widowed). The children listed were Brigida’s grandchildren and Maria’s children. Maria’s eldest daughter, Maria Antonia was 9 years old (born in 1862). Maria also had a four-year-old daughter, Clara, and a young son, Francisco, born in February, who was listed as six months old [U. S. Census Year: 1870; Census Place: Township 3 (Las Cruces Post Office), Santa Barbara, California, Roll M593-87; Page 25] Another son of Jose Solares would be born later.

Angel and Rafael in the 1870 Census

Angel’s family was listed in the 1870 census in Household 328 as “Barbara Angel,” The first person listed may have been Barbara, an Indigenous woman who was 56 and was probably baptized on Dec. 4, 1818 at Santa Ynez Mission [Santa Ynez Baptism #1065]. Then on the next line, Tomasa was crossed out and this is where Angel was seemingly tallied as a 60-year-old man and a day laborer who owned real estate valued at $375 and personal estate valued at $350.

In the next household [#329] lived 62-year-old Tomasa who “keeps house.” She is believed to be the wife of Angel and she had been baptized on December 30, 1812 at Santa Ynez [Santa Ynez Mission Baptism #808]. Two of Tomasa and Angel’s sons, Jose D. and Estevan, were also listed in Household 329. Jose D., age 21, had been baptized on January 11, 1848 [Santa Ynez Mission Baptism #1586] and Estevan was baptized on Dec. 26, 1849 [Santa Ynez Mission Baptism #1622]. The oldest son of the three, Alberto, 23 years of age, was probably Juan, who was baptized on July 12, 1845 [Santa Ynez Mission Baptism #1553].

Living in Household 330 was one “Juan Rafael,” a 43-year-old day laborer who owned real estate valued at $500 and personal estate at $750. It seems clear that this is Chief Rafael. His actual age was 48 years since he was born in 1822. Rafael’s 35-year-old wife was Maria, and his 25-year-old son Manuel was a “cattle herder.” Manuel would be married to Maria Refugia two years later in 1872. Although Manuel was not known as Solares yet, this is presumably why Maria Refugio later became Maria Solares.

The Santa Ynez Tribe in the 1880 Census

According to Father Zephyrin Engelhardt, “white settlers [in the Santa Ynez area] gradually increased in numbers” by the 1880s. At the same time, “the neophyte Indian population was steadily approaching extinction,” thanks, in part to “the white man’s whiskey.”[49]

In the 1880 census, Chief Rafael was the 50-year-old acknowledged head of a large household in Ballard [1880 Census, Ballard, Santa Barbara, Roll 81, Page 558D, Enumeration District 085]. Rafael’s older brother Anjel (Angel) was now 70 years old. Listed as “squaw” were 40-year-old Gilla and 50-year-old Tomasa, the wife of Angel. Farther down in the household was 23-year-old Jose Dolores, a soon-to-be chief. Forty-year-old Maria [Solares] was also listed as a squaw and was the mother of 16-year-old Francisco. It is believed that she was widowed at this time.

The Sale of College Rancho

In 1880, Archbishop Alemany decided to divide the College Rancho so that he could rent small tracts to settlers. The rancho had land that could sell for as much as $150 per acre for the finest improved land.[50] In 1881, after Congress approved the sale, Archbishop Alemany sold 20,000 acres of the College Rancho and turned over the other 16,000 acres to the Catholic Bishop of Monterey, Bishop Francis Mora.[51]

Settlers who were interested in putting down roots in the area were allowed to purchase tracts of land selling for between $6 and $15 per acre. In late 1882, Bishop Mora gave each settler one free lot in the town if the settler purchased an additional lot for $15. The new settlement was originally to be named “Sagunto”, in honor of Bishop Mora’s birthplace in Spain. Later, however, “Sagunto” became the name of the main street, but it was decided to call the new town Santa Inés (Saint Agnes), which was to be built around Old Mission Santa Inés. Since the settlers did not know Spanish, they spelled “Inés” as “Ynez.”[52]

The Founding of Santa Ynez (1882)

On December 11, 1882, Santa Barbara’s newspaper, The Morning Express announced the “birth of a new town in the Santa Ynez Valley” in an article dated December 1, 1882.[53] Santa Ynez grew in the next few years into a town with a post office, saloons, and many homes. A rivalry was quickly established between the Valley's first town, Ballard, and the new town of Santa Ynez. By 1889, the Town of Santa Ynez had a population of about 400.[54]

The Santa Ynez Land and Improvement Company Acquires College Ranch

According to The Lompoc Record of 19 November 1887 [Page 2], the Santa Ynez Land and Improvement Company had purchased the College Ranch and other nearby properties. In fact, on December 7, 1887, The Morning Press reported that the Santa Ynez Land and Improvement Company had published a 6” by 9” pamphlet that was “one of the handsomest advertising books we have ever seen.”[55] Soon after advertisements appeared in The Independent stating that the lands of the College ranch had been segregated into tracts of from 10 to 1,000 acres in area and were now “for sale at low prices and upon liberal terms.”[56] The Santa Ynez Land and Improvement Company would play a key role in the Santa Ynez saga during the early 1900s.

The Death of Chief Rafael (1890)

On Sept. 6,1890, a priest at Santa Ynez Mission gave a Christian burial to the body of Rafael, described as “Indian chief” who was 68 years of age. He had received the sacraments before his death. It was noted that for sixty years, he had “attended and served mass, rung the bells” and “he died full of grace” [Santa Ynez Burial #2077]. The burial record that paid tribute to Chief Rafael has been reproduced below:

The Life of Old Rafael

According to the Santa Ynez Valley News, Old Rafael was considered the “one-time captain (chief)” of Santa Ynez, stating that he was remembered assisting in “caring for the interior of the church during its most neglected period, late in the nineteenth century.” In fact, worried about the neglect, Old Rafael took down the Saint Agnes statue of the mission and had it cleaned and repaired after someone had shot buckshot into it.[57]

According to his biography in Breath of the Sun, Rafael had fathered 13 children, all of which died before he did. He was a noted dancer and an antap [a spiritual person] who performed at Captain Pomposa’s fiesta in 1869. He was considered alcade at the Santa Ynez Mission in the 1850s. The Donahue family who arrived at Santa Ynez on All Soul’s Day in 1882 saw that 150 Indians were celebrating the feast day, commenting that “Rafael, a very fine and dignified old Indian who ruled his people in tribal and religious matters.”[58]

Origin of the Name “Zanja Cota Indians”

During the latter half of the Nineteenth Century, the Santa Ynez Indians became known as the Zanja Cota Indians. The Indians had been making their homes along the Zanja Cota Creek which had been the property of Joaquin Cota, a member of the illustrious Cota family that owned Ranch Santa Rosa. Joaquin Cota built the ditch connecting the stream with California’s first grist-mil built in 1820 by Joseph Chapman.[59]

The Smiley Commission Report (1891)

On January 12, 1891, the U.S. Congress adopted the Mission Indian Relief Act of 1891 which established the Smiley Commission to report on the status of the Mission Indians of California. The Act created a commission to carry out the Act’s mandate. Section 2 of the Act provides: “It shall be the duty of said Commission to select a reservation for each band or village of the Mission Indians residing within said State, which reservation shall include, as far as practicable, the lands and villages which have been in actual occupation and possession of said Indians, which shall be sufficient in extent to meet their requirements.”[60] President Benjamin Harrison by Executive Order adopted the conclusions of the 1891 Smiley Commission on December 29, 1891.

The 1891 Report of the Smiley Commission verified that about 35 descendants of the Santa Ynez Indians lived along the Zanja de Cota Creek near the town of Santa Ynez. According to the Smiley Report, “within the limits of the College Grant, in Santa Barbara County, in the Canada de la Cota, is an Indian village composed of some fifteen families.” These families had occupied this area since about 1835 immediately after the Secularization Act had taken place. Grants of land had been made to several neophytes by Governor in the College Grant, but they could not be found in the Mexican record.” There had also been “abundant evidences of a long occupancy… by a much larger number of Indians.”[61]

With regard to the legal rights of the Santa Ynez Indians to the land, the report also stated that “The present owners of the grant, while maintaining that the Indians had no legal rights which they will recognize, emphatically declare that they will protect and maintain to the fullest extent their equitable rights. They declare these Indians shall never be disturbed in their occupancy and use of the lands on which they now live, if they persist in their wish to say where they are, or they will, preferably, deed to the Secretary of the Interior, in trust for them, five acres of good land, to each family, pipe to it a sufficiency of water for agricultural and domestic purposes, and build for each family a comfortable two-room frame house.” [62]

After the Smiley Commission Report, the Indian Agent from the Tule River Agency began negotiation with the Catholic Church, to establish a permanent reservation for the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash. Around the same time (1893), the American illustrator, Henry Chapman Ford – who created depictions of the California’s missions – wrote:[63]

They occupy lands along the Cota Creek… This tract could not be sold or mortgaged , but was to be held as homes, and even a residence in other places did not forfeit the right of the descendants to a home there. This right was acknowledged by the Mexican government and also later, by the United States. Several attempts have been made to dislodge the Indians, but their rights have been maintained up to this period.

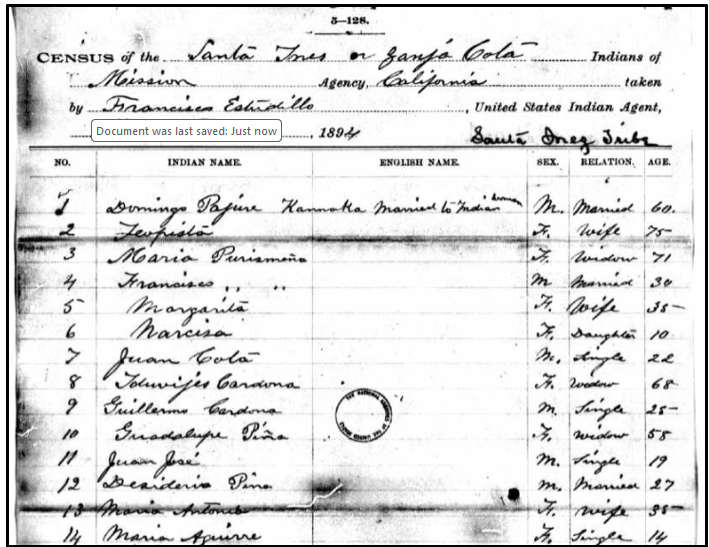

The Santa Ynez Mission Indians in the 1894-1895 Census

On June 21, 1894, The Highland Citrus Belt reported that the “census of the Mission Indians [was] being taken” but was “not yet completed.” Mr. Francisco Estudillo, the Indian agent for Southern California, had told the newspaper that he estimated the number of California Indians “at about 5,000.” However, he also noted that “the younger generation was indulging in dissipation.” He stated that “the young men drink to excess, and among women there is an awful immorality.” But he praised the older generation for having “marvelous tenacity of life.”[64]

The annual Indian census rolls were compiled by agents for the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) and mandated by the Act of July 4, 1884 (23 Stat. 76, 98). The Act stated “that hereafter each Indian agent be required, in his annual report, to submit a census of the Indians at his agency or upon the reservation under his charge.” A directive in 1885 (Circular 148) told agents to show the Indian name, the English name, Relationship, Sex, and Age.

On October 14, 1894, Estudillo arrived in Santa Ynez to tally the recognized members of the Santa Ynez tribe. By the time he had finished, there were 66 persons tallied, including 27 males and 39 females [U.S. Indian Census, 1895, Roll 258, Mission Tule River (1894-1897), at Ancestry.com, Images 180-182 of 637]. It should be noted that the census may have been taken in 1894 but it was officially regarded as the 1895 Indian Census.

The First Quadrant

On the first quadrant of the two pages listing the Santa Ynez Mission Indians in the 1894-1895 census, we see the names of people who would become relevant later. The No. 2 person listed was Teopista, the 75-year-old wife who was married to No. 1, 60-year-old Domingo Pajure [aka Pajury]. Teopista would be one of the five people listed in the 1903 Santa Ynez Land Deed as representing one of the original five families. Listed as No. 8 was Iduvijes [Eduviges] Cardona, a 68-year-old female who would also be listed as one of the five original families in the 1903 land deed. Listed as No. 12 and 13, Desiderio Pina was the son-in-law of Maria Solares and his wife, Maria Antonia [aka Ortega and Aguirre], was the eldest daughter of Maria Solares and the mother of numerous Piña children and of Maria Aguirre (through her first husband, Trinidad Aguirre).

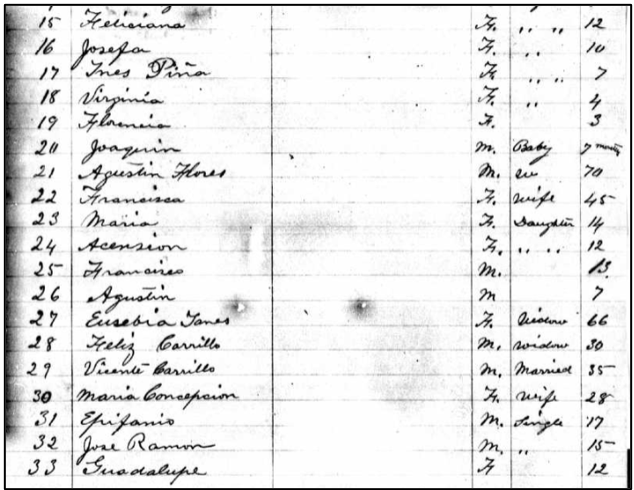

The Second Quadrant

On the second quadrant of the Santa Ynez families from the 1894-1895 census, we see many of the children of Desiderio Piña and Maria Antonia [Ortega] who are also the grandchildren of Maria Solares. Number 28 is 30-year-old Feliz Carrillo, who was already a widower and whose children had preceded him in death. Number 29 was Feliz’ brother, 35-year-old Vicente Carrillo. The Carrillo brothers were among the “five original Santa Ynez families” referred to in the 1903 land deed [to be discussed later].

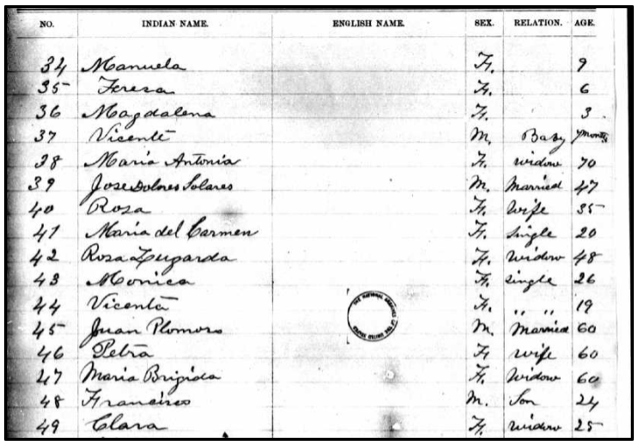

The Third Quadrant

In the third quadrant of the 1894-1895 Indian census for Santa Ynez we see that No. 39 is Jose Dolores Solares, a 47-year-old married man who would serve as chief around this time. Listed as Number 47 is the 60-year-old widow “Maria Brigida,” which was actually Maria Refugio using the name of her deceased mother. In the next two census schedules [1896 and 1897], Maria Solares would continue to call herself “Maria Brigida.” However, from 1898 until her death in 1923, Maria Solares would generally be tallied as “Maria Refugio Solares.” Two of her children followed her name: Francisco (No. 48) and Clara (No. 49). Clara’s name was also followed by her three children, Ysabel, Sisto (Sixto) and Petra, the grandchildren of Brigida (Maria Refugio), who are seen in Quadrant 4.

The Fourth Quadrant

On the fourth and last quadrant, we see Jose Solares (No. 53) and Fernando Ortega (No. 54) and his entire family [one wife and seven children]. Fernando’s great-great-grandfather, Jose Francisco Ortega, had begun occupying the area that became known as the Land Grant of the Nuestra Señora del Refugio Rancho as early as 1791 when the Indigenous people were the only inhabitants in this area. The Ortega family developed this rancho as a grazing area for their families’ livestock. In their 1827 testimony, the Ortega family members stated that they had received permission to establish a rancho in November 1794. Numerous members of the Ortega family were baptized, married, and buried in the Santa Ynez Mission since its establishment in 1804.

A Reflection on the Decline of the Mission Indians

On January 26, 1895, an article entitled “The Decline of the Mission Indians: Was It The Fault of the Padres,” asked what became of the 20,000 Indian “proselytes” (neophytes) and “the probable five or six thousand aborigines who had not been christianized?” The article stated that in twenty years, 15,000 to 18,000 had disappeared, and their numbers had “been steadily decreasing ever since.”[65]

The article stated that “the missionary work of the Catholic Church has not always been of a beneficent character. But the zealous padres… seem to have been moved by a spirit of high devotion to truth, and a sincere desire to carry the blessings of religion and civilization” to the Indians. However, the article also stated that “The Indian neophytes were little better than slaves, perhaps, and they may often have been ‘converted’ by force.”[66]

The 1896 to 1898 Indian Censuses

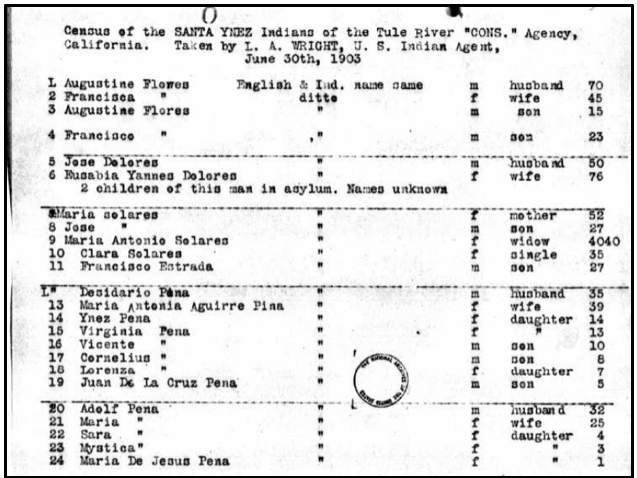

For the next few years, the Santa Ynez Mission Indian population would barely grow. On July 4, 1896, the Indian Census for the Santa Ynez Mission Indians was taken and revealed that there were still 66 members of the tribe in the year [U.S. Indian Census, 1897, Roll 258, Mission Tule River (1894-1897), at Ancestry.com, Images 396-397 of 637].

In June 1897, the Indian Census was taken was referred to as the “Santa Ynez Reservation” for the first time. There were 66 members of the Santa Ynez Mission Indians in that year [U.S. Indian Census, 1897, Roll 258, Mission Tule River (1894-1897), at Ancestry.com, Images 499-500 of 637]. The next census was taken on April 30, 1898 and recorded 67 members of the Santa Ynez Mission Indians [U.S. Indian Census, 1898, Roll 259, Mission Tule River (1898-1903), at Ancestry.com, Images 124-125 of 740].

During this time, the members of the Santa Ynez Band of Mission Indians resided on land that was owned by the Roman Catholic Church, but tensions between the Catholic Church and the Indians were growing more tense, especially because Bishop Mora was interested in selling much of the land to out-of-state settlers [mainly from Iowa and Illinois]. On October 15, Bishop Mora’s agent had received word that the representative of a colony of one hundred families from Iowa was at Santa Ynez in preparation to close a contract to purchase land for colony purposes.[67] But this contract was not closed after all.

Court Actions Against Zanja Cota Inhabitants

According to the Santa Barbara Independent, 17 February 1896, Bishop Francis Mora of Monterey began a suit in Superior Court against Francisca Zamora Flores, Augustin Zamora Flores and Jose Sotares [probably Jose Solares]. Bishop Mora, as the plaintiff, was the owner of the lands in the Zanja Cota tract and the defendants claimed an interest in this land, and this lawsuit was made to enjoin them from asserting any claim. A similar suit against Maria Antonia Pina [the daughter of Maria Solares] and Solomon Cota had also been instituted by the same plaintiff.[68]

On June 14, Jarret T. Richards and Ed C. Tallant filed a complaint against Inocente Jose Cota, Manuel Cordero, Thomas Del Valle and two unknown persons, praying judgment against them for the restitution of a part of Rancho Nuestra Señora del Refugio, and costs of suit.[69] At the same time, Jarret T. Richards and Edward C. Tallant also sued Guillermo Cordero and two unknown defendants (John Doe and Richard Roe). The plaintiffs stated that on March 1, 1897, the defendants “wrongfully and unlawfully” entered into the defendant’s property and ejected and ousted the plaintiffs therefrom. From that day, the defendants “wrongfully and unlawfully withheld and still and now wrongfully withhold the possession thereof from the plaintiffs.”[70]

The two cases went to trial on December 8, 1897.[71] Both cases were tried, argued and submitted to the Superior Court on December 11. The Court found that that the allegations in the complaint were true and found “that the plaintiffs are entitled to judgment for the restitution of the premises described in the complaint, and for their costs of suit. It was also stated that “the defendant has no right, title or interest in” the property.[72]

The Beginning of The Church Lawsuit (1897)

It is apparent that numerous Santa Ynez Indians had entered church territory over a period of a few years and refused to be ejected. It was obvious to the Catholic Bishop that he would have to take action that would encompass the entire Santa Ynez Mission Indian organization. According to The Santa Maria Times, on December 16, 1897, a notice of appearance of defendants was filed with County Clerk H.H. Doyle in the quit-claim suit entitled the Roman Catholic Bishop of Monterey vs. Salomon Cota, et al., or more properly, the Sanja Cota Indians. The tribe was occupying a tract of land near the town of Santa Ynez. The Mission Indians were represented by Frank D. Lewis, Esquire, United States special attorney for Mission Indians.[73]

In the early 1890s, a contract had been made for the sale of College Ranch lots to some German colonists, but it was not carried out because the Germans pointed out that “the land was subject to the undefined rights of the Mission Indians.”[74] According to California law at the time, the rights of the Indians permitted them to occupy continuously part of the rancho and to use water from the Sanja de Cota Creek, which ran across the ranch, “as they needed for domestic purposes, pasturage and irrigation of the lands occupied by them.” The Bishop, after losing this sale to the Germans, decided that he would have to quiet the title to the rancho.[75]

The Church Lawsuit Is Filed (1897)

With the continuing occupation of Church property putting a cloud over the property, Bishop Mora engaged Canfield and Starubck to bring an action to resolve this issue. In the so-called Church Lawsuit, Bishop Francis Mora, the Catholic Bishop of Monterey-Los Angeles, filed a lawsuit against individual Santa Ynez tribal members in a “quitclaim deed lawsuit” concerning about 11,500 acres of the Rancho Canada de los Piños (the College Rancho). With this lawsuit, Bishop Mora's office wanted to establish that the Church was, in fact, the true owner of the land. Actually a “quitclaim deed lawsuit” is a misnomer. It is better known today as a “quiet title action” which is a lawsuit that is filed to resolve disputes on a property’s titles.

However, although Bishop Mora first initiated the lawsuit, he himself had left the region and the United States to return to the land of his birth, Spain.[76] Bishop Francis Mora (1827-1905) served as the Bishop of Monterey-Los Angeles from 1878 to 1896. He was succeeded by Bishop George Montgomery, who served as bishop of Monterey and Los Angeles from 1896 to 1907.

In a notice published in The Morning Press on August 3, 1898, the Roman Catholic Bishop of Monterey made his case against Cota et al, stating that “this action is brought by said plaintiff to determine, settle and establish the boundaries” of the rancho in question which is “subject to the common and general right of occupancy of the band or village of Mission Indians known as the Santa Ynez Indians.” The Bishop referenced a deed of February 8, 1882 in stating that the “said plaintiff now claims to be the owner of said parts or portions of the said Rancho.”[77] This “Notice” was repeatedly published in the local newspapers in 1898. The complete defendant list for the Church Lawsuit is shown as follows:

In essence, all the defendants named were occupants of the Santa Ynez Reservation, as published in the annual Indian census. It was stated in the complaint that the defendants listed above were “a sole corporation existing first under and by virtue of the laws of the Republic.” They were known as “Neophytes” and claimed “general and common right of occupancy” of Canada de los Pinos, also known as College Rancho. In several places, the defendants are described as “all and every one of them members of said band or village of Santa Ynez Indians and reside on said portion”